Review: Rail by Kai Carlson-Wee

Reviewed by Tyler Robert Sheldon

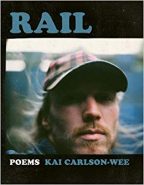

Rail

Poetry by Kai Carlson-Wee

BOA Editions, April 2018

$16.00, 104 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1942683582

Kai Carlson-Wee’s debut poetry collection Rail—a brave examination of the self through the lenses of travel, desperation, and depression—is an exodus from old identity and a restless search for new signifiers of self. The collection opens with an epigraph from songwriter Townes Van Zandt: “White freightliner / won’t you steal away my mind.” Carlson-Wee reveals a haunted past that gradually takes shape in these poems, aided by similar freightliners. The first, titular poem is sensuous in its admission of shaky identity: “I find it here in the wild alfalfa, head full / of antipsychotics and blue rain. Twenty years old / on a freight train riding the soy fields / into the night.” Like many other poems in this collection, “Rail” draws parallels between the self and the surrounding world through sound and image, where colors or descriptions help to define the narrators’ state of mind. These deft connections surface first in that blue rain, so similar to the melancholy that begins the book. They resurface later in the poem as well, when the speaker is “Staring out west at the stars / of our gods and the lonely dark stars of our hearts.” Shaped by the world speeding by around the train or falling away underfoot, the narrator’s identity shifts repeatedly throughout the collection.

These parallels soon turn visceral and immediate, notably in “Depression.” A gritty representation of the condition as a whole, this poem imports the surrounding world in a surrealist mode: “I felt the roof of my head break and clatter / to the floor . . . / Days fall back / inside themselves like water.” Juxtaposing a violent image with a softer one, the poem uses both to signify a spiral of flat hopelessness; this technique repeats at the end of the poem. Perhaps its most arresting moment, here two pastoral images are subverted by a bleak ending line: “the oak leaves fall and linger in the wind, / the swallows leave the shadow for the bridge / and the carp float dead in the metal grates below.” These dead carp make clear that everything is far from all right.

The narrator lets us into morning routine with “Mental Health,” a title that becomes the lens through which the poem is constructed; every image is colored by that label. The poem begins, “One pill in the morning with breakfast. Orange juice / and oatmeal . . . / One multivitamin with extra niacin for / stress relief, natural.” This list poem, at first mundane, soon morphs into a sequence of reminders, each signifying internal disquiet: “The man behind you selling a rock of crack / to a younger man, homeless . . . / Open your backpack / and take out a racquetball. Squeeze it between your / thighs and remember to count your breaths.” The sustained syntax here (“younger man, homeless”) allows this poem to maintain its list framework, but the unusual routines hint at the mental space the narrator occupies. The poem concludes, “This is the way your day begins.” By so doing, the poem informs the rest of Rail.

Later poems show the speaker in sounder emotional places. “Crystal Meth” demonstrates how the narrator filters the world as he takes in what good he can: “We are held in a light so perfect it grows inconsistent,” he marvels. “You could see it as a dream, or you could see it / as dreaming.” The poem, dedicated to a woman the narrator has known, is uplifting but also somber in how it arrives at that happier space. The speaker admits, “love is a field we measure between us . . . / A tower of light we keep chasing away / from a cloud.” As with this relationship, the undercurrent of Rail is often an attempt to outmaneuver the darkness—through whatever means necessary. For Carlson-Wee, these uplifting moments come at a price, which the narrator makes clear in poem after poem.

That price comes to light more explicitly in “American Freight,” one of this collection’s longer poems. Aboard a train, the narrator remembers how “[t]he antipsychotics I took that year made the world / inside me sublime. My eyes moved over the shape of a face, / the delicate wind in a tree.” This connection to the world, rare and mysterious, is tempered by strict limitations on thought: “I felt nothing. I wrote no poems. / The language of beauty divided itself into basic descriptions / of fact.” The medication that saves the narrator’s mind also chains it to grayed-out linear thought, a death knell for creativity. For this speaker, excavating a healthier new self from the from the colorful and deadly old is risky business.

This complicated relationship to the outside world is shown perhaps most clearly in “Titanic,” where the speaker and his brother (who is featured in many of these poems) find relief from their travels at the movie theater: “The spirit is not broken by cold. By the blowing snow / or the shattered bone . . . / The spirit / is broken by something else,” the narrator confides. He clarifies this other element:

Lull of shame in your younger brother’s voice.

[. . .] Hoping to sleep in the dark back row

where the ticket-boy might not check [. . .]

The strain in our eyes from going the last two nights

without sleep.

Thus, even brief moments of happiness are punctuated by considerations unique to the speaker that keep him from ever truly gaining contentment. The narrator, like the ship of the poem’s title, must contend with a shaky future and fight off seemingly inevitable ruin.

The ending of Rail shows that the self is eternal, just like the universal search to find it. The speaker links the self to another uncatchable element, perhaps the most enigmatic in nature. He muses, “although the soul is a joke we tell / to the part of ourselves we can touch, / it’s only because the soul is a fire, and laughs / at our sorrow, and has already survived us.” Fire, the ultimate signifier in this collection, denotes the temporality of life and permanence of its impact. These elements and others speed through Rail with the force of a freightliner, revealing at last the burning glow of the self.

Tyler Robert Sheldon’s newest books are Driving Together (Meadowlark Books, 2018) and Consolation Prize (Finishing Line Press, 2018). He received the 2016 Charles E. Walton Essay Award and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His poetry, fiction, and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in the Los Angeles Review, the Midwest Quarterly, Pleiades, Quiddity, the Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and other venues. Sheldon holds an MA in English from Emporia State University and is an MFA candidate at McNeese State University. He lives in Baton Rouge.

Leave a Reply