Review: God, the Moon, and Other Megafauna by Kellie Wells

Reviewed by Maggie Trapp

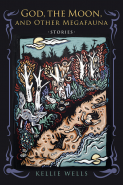

God, the Moon, and Other Megafauna

Stories by Kellie Wells

University of Notre Dame Press, 2017

$50.00, 192 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0268102258

A severed arm still wearing an expensive bracelet, a widowed mer-creature mourning her earth-bound husband, Time impishly personified and dating God, a miniature funambulist easing dolorous spectators by drinking in their sorrows, a number of states gabbing and gossiping and excluding a much-maligned Kansas, twin children living in a cellar all nine years of their lives and who are, according to their father, “as susceptible to spoilage as butter.” You know you’ve entered the world of a Kellie Wells story when you find yourself up close and personal with the lovably grotesque and the monumentally off-kilter. God, the Moon, and Other Megafauna is a collection of stories that feel like fables. Wells’s fabulism is a riot of dumbfounding images, discomposing metaphors, and gorgeous lines, a bewitched covert of droll, rich figures and scenes. Her obvious regard for her outlandish characters is matched only by her lovingly crafted turns of phrase. Wells’s is mandarin, tortuous prose scaffolded by periodic sentences, baroque figurations, fantastical conceits, and daft-yet-somber moments.

Many lines in these stories feel tossed off, they are so easily offered. But what announces itself as an aside is often in fact strange, surprising, and complex. Wells’s prose makes you double back in wonder. We read about fairy-tale–like characters and their unnerving quiddities, allegorical entities in all their endearing grotesqueries, and misfit humans who yearn for connection. All of this is conveyed in Wells’s disarming, wry, often screwball prose. When we read passages like, “The river, that was a good one. Her mother had hated all bodies of water, not least of all her own,” we know we’re in the hands of a writer with a dry, waggish sensibility.

Wells wins us over with her off-center similes and her madcap perspective as we read selections such as, “I looked at his front teeth, which overlapped as if huddling for warmth,” and, “Contrary to popular belief, Time, a fretful traveler, never flies, but she does enjoy walking. She believes it impolite to arrive at a destination too quickly. Sometimes even bicycling gives her the bends,” and, “On God and Time’s first date, they went to a slasher film, God’s choice, and God gasped five seconds before every out-of-nowhere chop of the ax. A man sitting in front of them turned around and glowered at God, who smiled apologetically, and then, midway through the movie, the man made a show of springing from his seat, throwing a snarl behind him, and stomping up the aisle. ‘Agnostic,’ God whispered to Time and shrugged.”

Wells’s prose calls to mind Elizabeth McCracken’s playful, lush, and startling work. Like McCracken, Wells blends the lure of the sideshow with the pull of fable and fairy tale viewed through a lens of slapstick and relayed via clever, startling prose. Wells draws us in with her smart, surprising turns of phrase, making us care about her curious characters’ moments of kinship and wonder.

We know that the peculiar is prized as much as the affecting when we read lines like,

Love, too, comes and goes like an empty bag snagged on a stiff wind, and because the distance between you and love, like the distance between a man and a clever tortoise, can always be halved, it is a destination that can never be reached. The woman knows her father’s body is resting against hers, but she can feel only air around her, encircling the discrete container that shields the yearning soul from insurmountable intimacy.

Wells drops us headlong into a welter of incontinent language and extravagant images that bore into us, piercing us with an uncanny yet comforting madness. As we read these stories we are keenly aware of their made-ness—they are cleverly crafted to an extreme degree. Yet we easily get carried up and into into these gorgeous worlds where the absurd and the incredible reveal to us the recognizable ways in which we all yearn to be truly seen.

Wells’s are stories of love and loss, of sympathetic oddities and compelling freaks. They contain scenes seemingly lifted from the cover of National Enquirer in the way that they beggar description and defy belief. These are stories that certainly necessitate a willing suspension of disbelief. Yet as we read them it becomes clear that the fantastic in Wells’s writing in fact tells us as much about our real lives as it does our imagined ones. What appears to be improbable is in fact, we come to realize, simply a compelling variation on our own familiar musings and wishes.

Maggie Trapp teaches writing and literature classes for UC Berkeley Extension.

Leave a Reply