Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise Review by Arthur Ivan Bravo

Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise

by Gary Panter

New York Review Comics, March 2021

$29.95, 104pp.

ISBN: 9781681375267

Book Review of New York Review Comics reprint of Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise by Arthur Ivan Bravo

Originally printed by Pantheon Press in 1988, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise has long since proven to be a premier chapter in the still ongoing adventures of multimedia artist Gary Panter’s alter-ego protagonist, “Jimbo.” Adventures in Paradise collects some of the character’s earliest appearances in Panter’s prolific comic-strip output, taken from Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s Raw, fabled punk/New Wave zine Slash, and other sources, all dating from 1978 to 1988.

Paradise introduces not only Jimbo, but other fictional characters and settings that would recur in Panter’s ensuing narratives, including the bonkers concept city of Dal-Tokyo: a Texan-Japanese co-founded Martian colony inhabited by an intergalactic populace. Likewise, the volume broaches themes Panter would continue to explore in his subsequent work—such as gentrification, nuclear war, consumerism, and a thoroughly capitalist post-war American culture seeping through into the everyday. Interestingly, the real-life inspiration for much of Panter’s characters, settings, and themes were the punk, New Wave, and indie/underground music scenes of Los Angeles and New York City in the 1980s. Paradise also notably documents the state of Panter’s craft—from his collage-like-constructed narratives, singular pen- and line-work, and all-pervasive DIY aesthetic.

As the fictional alter-ego and subsequent hero of many of Panter’s narratives, the character Jimbo was conceived in 1974 as a composite of many of the artist’s memories, acquaintances, and creative process. Among them his younger brother, comics characters Dennis the Menace, Joe Palooka, and Magnus, and even Panter’s own Choctaw heritage. Jimbo has since been extensively cited as a “punk everyman” and described as “primitive,” a “hillbilly,” an “American boy,” and more.

Adventures in Paradise begins with its titular character lost in monologue, questioning the boundaries between fantasy and reality, roaming a landscape of post-industrial devastation. A commentary on the hyper-modern/globalization of the era? Perhaps. In fact, the first place Jimbo visits is a new fast food joint in his neighborhood where robots telepathically read the customers’ minds to find out what they want to order without their stated permission. Disgusted by this, Jimbo leaves but is then chased around by a gang of mutants; he roams further before finding peace climbing the amazing cityscapes of Dal-Tokyo. There are sewer systems, bridges, towers, condominiums, skate parks, and advertisements showcasing real estate and other corporate entities appropriating and exploiting indie and underground sub-cultures for their own profit. Eventually, Jimbo is flushed out into the city’s waste system by a cleaning robot. Apart from the obvious allegorical motions of Jimbo’s semi-voluntary course through the city system, just as, if not more notable is the effective blurring between dream and reality. Quite often, the mundane readily gives way to the fantastical, and vice-versa, a frequently occurring element throughout Paradise.

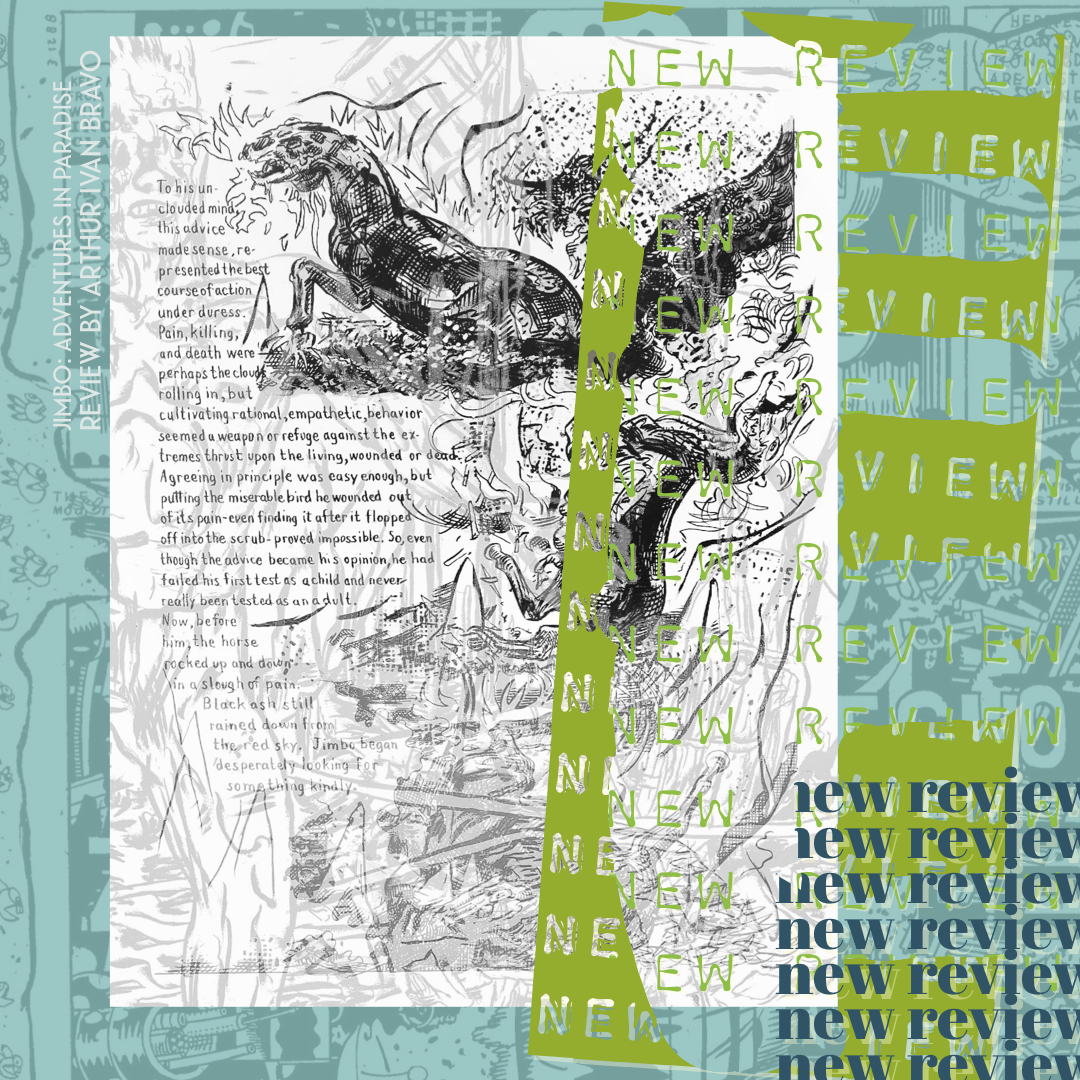

In one of Jimbo’s most memorable ordeals, he goes to a punk show and seems to drop acid. The narrative turn of events allows Panter to let loose with his tendency for filling entire panel spaces with all manner of minor characters, side-stories, and other details, all of which do more than just supplement flavor to the narrative, let alone expressing the true-to-life vibrancy of the LA punk scene at the time. His city streets, music venues, and drug trips are teeming with dystopic Mad Max-type vehicles, punks and aliens, ancient Egyptian and Mesoamerican iconographies, and hilariously rendered characters and dialogue. Elsewhere in his ensuing adventures through Paradise, Jimbo walks a terrifyingly monstrous Tyrannosaurus Rex/canine pet, clumsily woos his friend’s sister only to have to save her from cowardly cockroach kidnappers, and turns shaving into a near-mortal disaster. In an extended, experimental, and most powerfully profound climactic sequence, Jimbo survives a horrifying nuclear fallout, wherein he performs a thematic/narrative dialogue with a dying horse, reflecting Panter’s father’s reported love for the creature, as well as the anxiety of the twilight years of the Cold War during which the story was written and drawn.

The new printing of Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise by New York Review Comics will provide a welcome re-introduction for those waiting to discover Gary Panter’s work, his alter-ego hero Jimbo, and his abundantly amusing adventures. The reprint makes use of its ample magazine-size pages to highlight the singular particulars of Panter’s work, from his economic, or over-saturated, utilization of the entirety of his panel spaces with minor or side-details of all sorts, the non-linear expressive character of his line-work, the raw, crude, DIY aesthetic of his general pen-work as if to show off the labor inherent in it, his employment of elements from a wide array of different periods and styles from art history, and the overall thematic content explored. It stands as a fascinating, hilarious, but ultimately seminal document of pop culture, as the hyper-conscious 20th century hurtled towards its inevitable end, naively unaware of what was to follow.

Arthur Ivan Bravo is a writer and educator based in New York City. He writes about contemporary art, literature, music, and pop culture. His writing has been published by Vice, Interview, Dazed, and The Los Angeles Review of Books, among other publications.

Leave a Reply