Review: Vanishing Acts by Brian Barker

Reviewed by Roy White

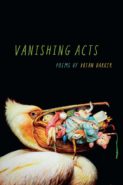

Vanishing Acts

Poems by Brian Barker

Southern Illinois University Press, March 2019

$15.95, 72 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0809337279

Many things are vanishing in Brian Barker’s Vanishing Acts: mountaintops removed for coal, towns drowned for hydroelectric power, endangered and extinct species, even “the lost cities of Earth” in a devastated future. This might suggest a tone of wistful elegy, but that is not it at all; instead the dominant emotion is anger, expressed through a kind of exuberant revulsion.

The book is full of gashes and mutilations, wounds and festering sores. In a wonderful left turn of phrase, a land agent promises that the mountaintop will come off clean, “like a hat or a scalp.” A man tortured by secret police is left with a hole in his head through which the ghosts of names seep out at night. An eagle chained to its perch has jumper cables running into its chest through a “crude surgical incision.” More than one character has facial blisters, including a man with “a tiny row of blue blisters….on his upper lip like a mustache of radioactive lice. It’s clear that these pathologies are a literalization of the cultural pathologies of violence and greed, but one also feels at times that Barker has a special fondness for the gross-out.

These are prose poems, set in blocks of justified text that suggest a Cartesian space where all the lines meet at logical right angles. The poems do not, of course, fulfill this promise; at their best, they veer off in doglegs of horrible whimsy, reminiscent of Russell Edson or Michael Bazzett, which prevent their political message from degenerating into lecture. In the quasi-title poem, “Vanishing Act,” an entire mountain has disappeared or been stolen. The townsmen leave in a search party and never come back, and their widows move into an old Victorian on the edge of town.

Some nights, when the devil drums his painted nails against the picture window, they can be spotted chasing him back across the wasteland to his hole, running barefoot over the cold, powdery cinders where all sound perishes.

The pleasure of the unexpected here combines with a particularly rich sonic texture (“the devil drums his painted nails against the picture window”).

Set against these mini-narratives of human exploitation and destruction are a collection of animal prophecies. Framed in an indefinite future tense, the animal poems offer a counterpoint, in many cases a counter-attack: when the oceans rise, sea anemones “will climb toward heaven on their one foot” and lobsters will “sit upright In armchairs, basking ceremoniously in the glow of reading lamps.” On the first day of spring, elk “will walk the crumbling highways into the cities of man.”

Though these animal pieces are driven forward by anaphora and illuminated by striking similes (“squatting in front of their burrows like belligerent doormen enduring an embolism”), they often feel like lists of concatenated items, and at a certain point one begins to tire under their accumulated weight. Perhaps a form that reflects their rhetorical structure would allow the reader more space here than the wall of block text does.

If the animal poems are distanced by the future tense, the human world of Vanishing Acts is also frequently remote. Beside the energy drinks and Facts of Life marathons we find villages inhabited by men with hats and women with shawls, not to mention harlots, knaves, and footmen. Even the secret police and executioners have a somewhat old-timey flavor, and the historical references lean toward Eastern Europe: Stalin, Mandelstam, an unnamed Slovenian poet. All this perhaps suggests a resonance with the wry tone and sober absurdity of some Eastern European antecedents…the Kafka of The Castle, Szymborska, and Herbert are the names that come to my mind, but there are likely others that would strike a reader better versed in those traditions.

“Science Fair,” which opens the book, illustrates the bitter verve with which Barker imports the remote and strange into our supposedly normal existence. Here is a Model T made of tin cans, with a Henry Ford dummy slumped in the front seat (the brown glue leaking from his wig is somehow characteristic). We follow a set of jumper cables out from under the hood, out of the school into a barren landscape, and up a slope of scree:

Here, a feverish Audubon in a bathrobe, his face pixelated with sweat, circles an eagle chained to a perch, jotting down measurements and notes. The cables disappear into a crude surgical incision in the center of the bird’s chest. “John James Audubon, the father of modern ornithology,” the teacher intones, wiping his spectacles with a dirty hankie.

Brian Barker is the author of three books of poems: The Animal Gospels, The Black Ocean (winner of the Crab Orchard Open Competition), and Vanishing Acts. His awards include an Academy of American Poets Prize and the 2009 Campbell Corner Poetry Prize. He is married to the poet Nicky Beer and teaches at the University of Colorado Denver, where he is a Poetry Editor of Copper Nickel.

Leave a Reply