Review: Un-American by Mandana Chaffa

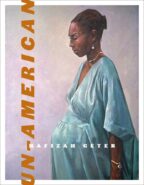

Un-American

Review by: Mandana Chaffa

Written by: Hafizah Geter

Written by: Hafizah Geter

Wesleyan University Press, September 2020

$15.95

104pp

ISBN: 9780819579812

How do we define ourselves? How are we defined by others? Hafizah Geter—like many who came to the United States as children—navigates the unsteady ground of immigrant identity: “I arrived, language’s orphan, / a two-citizen child, no country.” In Un-American, her debut poetry collection, Geter explores what it is to be bicultural by examining both the absence and presence of qualities, experiences, and language, with poems that are both timely and timeless.

The prologue, “Pledge,” is a poem in two separate columns, united only by the last line. Tight and full on the page, it’s a sharp contrast to the remainder of the collection, in which poems are spread out in a surfeit of space. That shift in the visual cortex indicates the verdant ground that this author explores, both intimate and expansive.

I am a test of how far a daughter’s memory can go

In the title poem, the reader considers what it is to be naturalized: how one may still not fit in and never be accepted, regardless of the idealistic national rhetoric to the contrary, “My grass-stained knees pledge allegiance / to a country that belongs to no one / I love.” That this country may accord immigrants legal citizenship, but often with a caveat, an asterisk like a melodious accent that will never fade, a door through which they will never be invited to walk, “I look for the ones like me and my sister / who, not born in this country, / can never be president.” Often immigrants are hyphenated Americans whose entity must be divided with neither existence ever complete. In her life and poetry, Geter is examining the flexibility to be authentically in both or several, where one doesn’t negate the other.

Before one can define what it is to be un-American, one must question who decides what is a good American. Are the parameters—like the high notes of our national anthem—so challenging that many are defined as lesser participants even as they serve as a critical part of the fabric of this nation? “Naturalized Citizen” reveals the unequal relationship in how this country embraces its citizens. Every immigrant who is urged to change their name to make it “easier” on others knows that the acceptance is qualified, that America’s love isn’t unconditional, and she does have favorites:

In America, no one would say her name

correctly. I watched it rust

beneath the salt of so many tongues

like a pile of crushed Chevys.

Names also loom large in this book: our given names and the names we give ourselves and those that others use to categorize and classify what—or who—shouldn’t be welcomed. Then there are words that can’t be translated at all, the ones that carry the weight of history and memory, and of possibility:

our names two familiar

sounds turned strange,

tightropes swaying,

in a colonial country.

One notes the duality of the word colonial in this context; America has a history of being both colonized and colonizer, the irony of disparate states that were formed on the premise of being un-British.

Geter’s examinations also reflect the degrees of separation even within the same family. In “Out of Africa,” the older sister’s experience is not the same as the younger’s. An age difference of three years results in different memories of Nigeria, which alter who and what each of them become. Understandably, memory plays a large role in this book, as well as in the émigré’s life: how it subtly alters the calibrations of what it is to be or to not be, and to own and to be owned in return.

The older she gets, the more I see

how her six years in Nigeria rival my three,

how the memory of the land wisps from the switch

of her wrists, how African she must seem

There are brutal choices for those who adopt a new country, and they are often complicated by parental desires about what should be remembered and what is forced into an attic underneath the weight of painful memories. In “The Leaving,” the narrator’s mother exhorts:

She whispered, leave

our language behind, afraid

of an old country

on my tongue.

Geter must equally contend with what it is to be Nigerian, though one imagines there’s not a similar trope of being un-Nigerian; it seems that only this nation repeatedly tests its citizenry on how “American” they are, what they are willing to forego in order to be accepted, to be worthy, to be one of us, and not them.

Geter serves up the nuances and the regrets of trying to connect with the entirety of her heritage by fashioning a narrative from memory and familial investigations. That she accomplishes this in the language of her adopted country offers its own echo of wistfulness, of the “un” that is in the title of the collection.

There are also a number of poems entitled “Testimony,”—written for Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Michael Garner, others—that call to mind the duality of the word’s meaning. Both legal proof of a fact or action and a form of individual documentation, these poems witness and judge atrocities in which the legal system and society have abnegated their responsibilities:

Mr. President it took one whole day

for me to die and even though I’m twelve and not afraid of the dark

I didn’t know there could be so much of it

or so many other boys here.

Especially heartrending is how the verses in these separate poems reflect a horrific repetition of the many murdered, their lives cut short, seeped into the amber waves of grain in this purported American dream become nightmare: “Officer, I heard that after so much blood, / the ground develops / a taste for it.”

The poems in Un-American are deeply personal and speak to universal emotions: the push-pull of belonging, the conflicts and comforts of family, the desire to shape one’s identity and narrative, which is the basis of American pioneer dreams, written by a remarkable poet who is creating her own country, her own language, her own story.

Mandana Chaffa is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Nowruz Journal, a periodical of Persian arts and letters that will launch in spring 2021, an Assistant Managing Editor at Split/Lip Press and a Daily Editor at Chicago Review of Books. Her essay “1,916 Days” is in My Shadow is My Skin: Voices from the Iranian Diaspora, (University of Texas Press, 2020) and she edited Roshi Rouzbehani’s limited-edition illustrated biography collection, 50 Inspiring Iranian Women (2020). Her writing has also appeared or is forthcoming in The Ploughshares Blog, Chicago Review of Books, The Rumpus, Split Lip Magazine, Asymptote, Rain Taxi, Jacket2, and elsewhere.

Leave a Reply