Review: Tracing the Horse by Diana Marie Delgado

Review by by Noel Quiñones

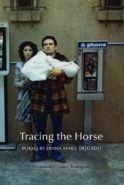

Tracing the Horse

Diana Marie Delgado

BOA Editions, September 2019.

$17.00; 112 pp.

ISBN: 978-1-942683-87-2

In Diana Marie Delgado’s debut collection Tracing the Horse (BOA Editions, 2019) these poems strike as hammers, ringing out the pain of returning again and again to what hurts us most. Delgado curates the landscape of hurt, offering a speaker caught within a cycle of familial and personal trauma ranging from physical violence to incarceration to drug addiction to rape. Set in the speaker’s hometown of San Gabriel Valley, Delgado outlines the colliding narratives of various Latinx family members as she tries to make sense of a deeply troubling childhood. Tracing the Horse, through constantly shifting character vignettes, a harrowingly intimate approach, and ruthlessly assertive verse, has no beginning and no end, rather only the speaker constantly, relentlessly outlining the shape of trauma.

In his forward to the collection, Luis J. Rodriguez rightfully asks us not to read Delgado’s work but to witness it. Delgado strikes at the burden and boundary of witness, each poem instructing us on how to read this work. In “They Chopped Down the Tree I Used to Lie Under and Count Stars With” she asks “When you see yourself is there an observer?” Witness is, therefore, a burden shared with the reader, but also one that honors the boundary of coping as an individual endeavor. Delgado’s opening poem “Little Swan,” establishes the parameters of her perspective: “Most nights I’m face to face with the stars. / No one is more afraid of this than me.” Tracing the Horse may invite us in, but we are stuck behind the glass erected by Delgado’s syntax. The speaker stands as premiere witness but not necessarily because she chooses to. The poem continues: “So I find places to lie down / and signify.” Delgado’s speaker is the translator of her family, the scribe who attaches language to experience in an effort to signify some kind of understanding. As witness and translator, she is both scarred by and obliged to spread the story of San Gabriel Valley. At various points the speaker is told by family members to “start this story,” “to draw your mother,” and to “decipher the speaker.” Delgado’s speaker is charged to tell this story; yet Delgado knows intimately that trauma communicates through multiple languages, never a clear final product but a shifting outline of its purposes.

Throughout Tracing the Horse, Delgado’s speaker moves between childhood and adulthood, between the internal and the external manifestations of trauma in an effort to convey it’s start-and-stop nature. In “The Sea Is Farther Than Thought” we are introduced to the speaker’s childhood coping method. A method that, at its onset, dismisses her own voice as the premiere form of communicating.

If the original tunnel of the body

is the mouth, I’ve never had one.

As a girl I kept suede horses

and a hairbrush inside a blond toy-box.

One day my face will refuse to turn away.

Some people like poison.

I kneeled every time I opened it.

The speaker translates the reverence she sees her family members give to the poison of drugs, and bestows it on her toy horse. She centers sight and touch here as she will one day grow up to face the trauma of her family. The horse is a central figure in this collection, taking on many personas from a toy figure above to the speaker’s mother to its literal animal form to men who commit sexual assault. Each form it takes expands its interpretation as a harbinger of trauma. Yet, the action accompanying it in the title is equally important: tracing. While obvious, any poetry collection is built on the capability of the written word to convey meaning. Yet at almost every turn Delgado pushes us to consider how trauma can be understood through multiple modes of comprehension: from reading to feeling to dancing to drawing to seeing. It is Delgado’s dedication to a true representation of hurt that allows the reader to bear witness to the insidious and cyclical nature of trauma.

Not only does Delgado convey her poems through various modes of comprehension but she does so by introducing various recurring characters, from her parents to El Scorpion to Wolf to the Devil to the Moon. She creates a landscape where “the Devil / can dance like a goddamn dream,” her brother “learned to read in the dark,” the speaker can write “on paper / at the bottom / of a pool,” and the moon can “tell the world what it means” through her. The speaker’s family members exist side by side with these abstract characters, blurring the lines of comprehension as trauma does so well. This is nowhere more apparent than in her title poem, “Tracing the Horse”:

I’m riding a horse I can’t stop drawing,

a wild one with a whip for a tail.

It’s a song in a dream

whose words burn

my hands like light.

In this opening we see the horse through multiple registers: the physical, the artistic, and the dreamlike. No register is less true than any other. While the horse’s various personas are haunting, the true terror Delgado invokes is the fact that trauma does not let the speaker escape the horse’s constant reinterpretation. With each return to the animal, Delgado’s speaker uncovers a new layer of understanding. It is the act of repetition itself that works as a coping mechanism for the adult speaker. The poem ends with: “I take a book home, read and return it; / ( ) / I never read the whole book, just parts, / words in a row, I read for feelings.” Delving into the book of San Gabriel Valley in one sitting is a terrifying thought to the adult speaker, something that has been carried over from childhood, and so she chooses to read it just in parts. In this way Delgado instructs us to read for feelings rather than a strict linear narrative in Tracing the Horse, therefore using the visual act of tracing to create a literary representation of trauma which invites us to bear intimate witness to the cyclical, and at times narratively undefinable, nature of trauma.

As the collection progresses, we see the adult version of the speaker more clearly. This is done through poems that take on a more vignette form, written in prose blocks. These narrative poems jump from scenes of the speaker’s grandfather’s reaction to going to hospice, to her father accosting her mother for trying to intervene in an assault, to a conversation between the speaker and an unknown lover about a possible child named Maria. These jumps cause a sort of whiplash, a constant inundation of characters, experiences, and traumas that further add to the landscape Delgado is determined to pay witness to. Yet in this hurt, Delgado acknowledges moments of clarity that grow from this constant cycling.

Delgado splits Tracing the Horse into three sections, allowing us a glimpse of the adult speaker’s coping mechanisms. The title poem ends the first section, instructing us to “read for feelings,” while “Dream Obituary” ends the second section, offering a path forward: “Now in the middle of my life / my journey is to forgive / everything that’s happened.” This sentiment is carried through in “Greenbriar Lane” where she writes “My job is to bring beautiful / things back to life” and in “Never Mind I’m Dead” which asks both the reader and the speaker’s family to “come back with me / to the ruins.” This older, wiser version of the speaker has a small and sparsely placed voice but one that adds another necessary layer to the portrait of trauma Delgado is drawing. While mainstream media may sell us a version of coping, one where our protagonist comes out the other side renewed after confronting their trauma, Delgado does not in engage in such a trivial representation. Trauma is an unending cycle–one that must be faced, and yet even then it does not simply resolve itself.

Purposefully inundated with characters and whiplashing in its approach to narrative, Delgado paints an incredibly accurate portrait of trauma. The hurt of San Gabriel Valley is an inescapable and unrelenting cycle, yet one which can be excavated and “signified” upon multiple returns. Her approach is made clear when we trace the through-line from her opening line to her closing line in “La Puente”: “Summers were horses traced on denim; my youth unfolding, / paper fan.” We began with an outright terror and end with a quieter terror. Each character, each experience is another ridge on the paper fan, an unfolding represented by an object which moves so fast it can become indistinguishable. While not without moments of reprieve, laughter, and even happiness, her narrative unearths trauma’s implicit denial of closure. Delgado intentionally places the pencil in our hand and narrates as we draw, outlining the shape of trauma as we quickly learn it will never become a finished portrait.

Noel Quiñones is a Puerto Rican writer, community organizer, and performer from the Bronx. His work has been published in POETRY, the Latin American Review, Rattle, Kweli Journal, and elsewhere. He is the founder and former director of Project X, a Bronx-based arts organization, and a current M.F.A. candidate at the University of Mississippi.

Leave a Reply