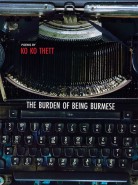

Review: The Burden of Being Burmese by Ko Ko Thett

The Burden of Being Burmese

Poems by Ko Ko Thett

Zephyr Press, October 2015

ISBN-13: 978-1938890161

$15.00; 101pp.

Reviewed by Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers

Ko Ko Thett’s The Burden of Being Burmese is prefaced with a quote from Shway Yoe’s The Burman, His Life and Notions: “When anything surprises or pleases a Burman he never fails to cry out, Amé—mother.” That claim echoes off surprising places in the book. The word “mother” is used sparingly in the volume, but the poems abound with a sense of primal seeking after origins, sources, and attachments. Thett circles themes of interconnection, history, destiny, and translatability. He defines the burden of being Burmese through a deep and expansive dive into the quotidian particulars of life as a Burmese national, an expat, a political person, and a poet.

Thett’s word play serves as the bedrock of every poem. He doesn’t capitalize any words in his poems and uses punctuation sparingly, making the voice seem intimate and close but never small. The line breaks do the heavy lifting. Phrasal divisions similar to breaths in spoken language are standard, so many lines have a meaning that builds, shifts, or changes interlineally. Often, Thett builds a structure of inversion or opposition, like in “after ‘the lie of art.’” Thett makes a series of thirty-eight interlocking statements, with key words in one line reversed in the next, beginning with “i hate walls that have eyes/i hate eyes that have walls” and ending with “i hate yours truly/i hate truly yours.” Thett embraces the possibilities in repetition. In “strawman story,” “strawman [in reverse],” and “a few ways to eat a city raw,” he builds and expands meanings line by line, throwing single words or whole lines into multiple contexts. In “a few ways to eat a city raw,” the opening lines say it all:

[when you end up somewhere you don’t want to be]

eat it like a durian

eat it like someone who’d puke at the mere mention of a durian

you are marooned on durian island

These poems emerge complex and interconnected as tesselations.

When Thett isn’t exploring the slipperiness of language and meaning at the word level, he’s looking for it in context. Thett goes where experiences are penetrable and shifting. In “my generation is best,” the speaker addresses the nostalgia of a “you” from the prior generation. After detailing the “you’s” laments for a mythic past, the speaker finally lists all the composers, poets, painters, and filmmakers of this other generation, noting all the work they might have created if not for the harsh realities of that very same past. But the speaker ends by addressing the “you’s” own stillborn future saying, “…and you yourself, if and only if… // yes, yes…i dig you, stop weeping… / your generation is best.” The tenderness of this admission turns the whole poem on its ear, reframing the typical inter-generational grousing into a commentary on something much more poignant. Thett uses this technique in other poems, such as “corpse flower blooms in washington,” where the final lines affect a moment of dislocation as perspectives shift.

Whether on the word level or via context, Thett is interested in voicing a dualism that acknowledges and advocates. In “the mandalay gazette 1885,” the speaker states,

true believers no longer know what comes first in their faith

the mad monk or the flighty boat

the porous border or the birth rate

the whoring media or the pimping state

buddha, dhamma or sangha

father, daughter or holy spirit

buy me, get my country free

In the poem’s slippery final line, the speaker’s words can be read as cynical statement or political plea. This kind of both/and language acknowledges baggage—a cultural history of colonization, political strife, trauma, and acceptance of pain—without taking away individual agency. In “the burden of being bama,” people are likewise depicted between hard, sometimes oppositional choices. But Thett suggests that, while people take their history with them, history isn’t quite the same thing as destiny and its weight doesn’t have to be silencing.

Thett’s poems are like eavesdropping through a shared wall. Ensconced in your own room, insulated by your own experience, sound barriers prove penetrable. Words and phrases layer into narrative; buses, buskers, and bureaucracies emerge from the humid heat of the imagination. As Thett says, being Burmese is chance, but his poems are an ecumenical burden, an essential and exact experience of their own.

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers’ work has been published in Gemini, The Missing Slate, The New Poet, Gulf Stream Literary Magazine, and The Burden of Light: Poems on Illness and Loss, edited by Tanya Chernov. A native of Pennsylvania, she currently resides in Buckingham, Virginia.

Leave a Reply