Review: Still-life with God by Cynthia Atkins

Reviewed by Michael T. Young

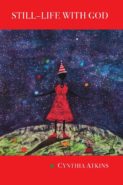

Still-life with God

poems by Cynthia Atkins

St. Julian Press, March 2020.

$16.00; 112 pp.

ISBN: 978-173023306

Like a Beethoven symphony, Cynthia Atkins’ latest collection depicts triumph through struggle. In this sense, it is a refreshingly hopeful book, though the success is hard won. The opening poem, “God is a Wishing Well,” sets the stage telling us that “trauma was my life in a gun shell.” There’s a faint echo of Hamlet’s “bounded in nutshell” in the line and this is significant, for the collection is a struggle toward an openly authentic self. What opposes that authenticity and creates the struggle is the God of the title.

God, as he typically appears within the collection, is not a divine figure. Rather, he’s the various kinds of authority we are taught to respect, the ever-present male violence in our culture, and forms of acceptance we are taught to pursue. God appears not only in the many titles of poems but within the poems as an unshaven drunk, a rapist, deranged powers “off their meds,” a tooth fairy with “nicotine on her breath.” These are memories that build into a repressed life, a “Tree of Life,” as in the poem so titled where

These limbs are the windows, a contour

of unplanned townships, each municipal

self you have lost along the way.

Poem after poem builds up the conflict between the world as given and the self it silences. Thus life is composed of all the elements of the self that are denied, improvisations of survival in a world hostile to it, the silences forced on the true voice. This is what comprises the still-life in the book’s title. “Still-life” comes from the French “nature morte” and means “dead nature.” Images of inanimate objects. This is what the self becomes in a world that manipulates it to its own ends: a dead nature propped up in a world of false gods. But that nature, that repressed self, doesn’t go away. Rather, it smolders under the surface. The struggle largely plays out as a tug-of-war between song and silence, the pain to give voice to the real story. As we’re told in “Letter to the Woman Who Had to Hang Up Her Coat,”

A voice that no one else

can hear is large and gangly

as a bomb in your throat.

Another form that struggle takes is in a desire to take part in story, to reimagine or rebuke certain received ideas and phrases, similar to that faint echo of Hamlet in the first poem. Take the following as example from “Domestic Terrorism,”

………………………………………………………The bad boys blast

firecrackers between your legs. Terror is not bliss—it is

invisible and dangerous. It brings hearts home in body bags.

It gags your own mouth with stones.

Here Rilke’s associative concept of terror and beauty from the 1st Duino Elegy is not remade, but implicitly denied, and justly so in a culture that appropriates female beauty for its own ends, contrary to the woman’s own desires. This battle with language and ideas over control of female identity pushes Atkins toward many linguistic risks. While not all of them succeed, most do and with a powerful payoff, which is a journey toward a redeemed self. The turn toward that redemption happens slowly, painfully, as the speaker confronts memories of violence and begins listening to the buried voices.

……………………………….My mother never warned about

real monsters. Through a crack in the door,

I saw her talking to air, a flirting

……….with the wrath of God.

In this poem, “Self-Portrait With Hermit Spider,” the speaker glimpses what sometimes happens behind closed doors, the anger against what holds the female identity back, all that denies the authentic self, “the wrath of God.” It’s a version of male violence and dominance that in other places is more overtly detailed as in “Left to Right,”

………………………………When there is no language

for human pain, guns are the jewelry of men.

Although language and violence here are opposed, the trajectory of the collection still requires honesty about language itself before its redemptive power can be invoked, for

I’ve learned that words matter, but words lie,

yes, they do.

This from the perfectly titled, “Before the Lies.” Admitting their potential for deception, they can then be reimagined in an art born of nature. This same poem tells us,

The earth opened to a place where language

hoards the silence, animals in a barn of breathing.

All the trauma stored as silence becomes a source of language, a song that is itself a mastery of the pain and history. In this context, the collection’s struggle finds rapid resolution. The final pages expand with a voice that shapes the air into a kind of web, like a spider, producing something protective and a source of nourishment. A goddess appears in the “Goddess in Purple Rain” (page 66). Here a woman in a laundromat dances and provides a musical release, where, “the stars allow me / to follow her.” In earlier poems there were holes in the stars, holes in the heavens, and they were always at a distance where they “tease and ridicule” (“In Handfuls”). But now they permit passage, perhaps even guidance.

The final poem, “God is a Myth,” finds the speaker fully emerged from the repressed regions, out in the open and realized. The speaker declares, “I never existed before this moment.” It is an earned conclusion to a collection that is full of struggle and song, a language that sings its pain and, in the singing, reclaims the repressed voice and redeems the suffering self.

Michael T. Young’s third full-length collection, The Infinite Doctrine of Water, was longlisted for the Julie Suk Award. His other collections are The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost andTranscriptions of Daylight. He received a fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. His chapbook, Living in the Counterpoint, received the Jean Pedrick Award from the New England Poetry Club. His poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in numerous journals including Ashville Poetry Review, Compulsive Reader, Gargoyle, Quiddity, Rattle, and The Smart Set. His poetry has been featured on Verse Daily and The Writer’s Almanac.

I am blown away by Michael T Young’s artful and beautifully written review of “Still-Life With God.”–I am so grateful to him and the Los Angeles Review for holding this coveted space—wow!