Review: Prayer Book for the Anxious by Josephine Yu

Reviewed by Kims Jacobs-Beck

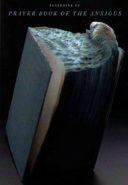

Prayer Book for the Anxious

Poems by Josephine Yu

Elixir Press, October 2016

$17.00, 96 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1932418583

Prayer Book for the Anxious is wry and playful, insightful and meditative. Overall, Yu’s poems work together to produce a memorable, introspective book. Through a blend of humor and empathy for her characters, Yu creates a space that is at once edgy, a bit unsettling, and yet offers the possibility of forgiveness and second chances. This tension between less than admirable human traits and grace deftly plays out the book’s themes.

The collection is divided into three sections: Apologia, with ten distinctly identified characters serving as narrators or subjects; Canticles, Maybe, with several poems using the names of saints, biblical characters, and religious forms of address such as psalm, prayer, proverb, plea; and Rustle of Offerings, focused on personal topics through a first-person narrator. Several poems with “Palm Leaf Manuscript” as part of their titles connect all three sections. The Palm Leaf Manuscripts introduce a non-Christian religious element, since such documents are south Asian in origin and were used for both religious and non-religious writing. Palm leaves also allude to Christianity, particularly to the Catholicism that runs underneath the book.

In Apologia, ten poems are narrated by characters identified by descriptive nouns and nominal phrases: the compulsive liar, the lepidopterist, the fortune teller, the loneliest man on earth, failed revolutionaries, the vindictive son of a bitch, the manic depressive, and the optimist. Most of these descriptors distill the character into a marginalized type, but each poem tells a much more complex tale. The opening poem, “The Compulsive Liar Apologizes to Her Therapist for Certain Fabrications and Omissions,” reveals this complexity. The poem opens with the liar dismissively describing the therapist and her office:

Attic office, turquoise carpet, rock fountain

on the end table, its drowned gurgle—

I admit at first these filled me with contempt,

and the Madame Alexander dolls in the pram

made me uneasy. But I stayed out of pity

for your heart-embroidered vest

and your eagerness as you leaned toward me,

pen poised above a clipboard.

Yu immediately makes clear that this narrator is both condescending and refreshingly, even admirably, honest about her condescension. The narrator shifts from a sarcastic, above-it-all cynicism to the kind of breakthrough one expects to have in therapy–recognizing one’s own weaknesses. As the poem continues, the liar admits to faking everything she has told the therapist, including lying about dreams and making fun of the therapist for her earnest decoding of dream symbols. The tone turns from sardonic to sincere when she admits that she should have shared her “only” dream, the familiar one of crumbling teeth, and her desire for a gold tooth, “a molar, just one, anchored in my jaw,” which is located, she imagines, “near the beginning of words, like a secret / or a blunt pain.” Other poems in this section similarly surprise the reader with unexpected vulnerability buried under each narrator’s posturing. These are unreliable narrators, yet they also tell truths, often by telling on themselves.

Canticles, Maybe mixes religion with sex (“Conception Psalm”), money (“Middle Class Love Song”), the restive nature of Americans (“Prayer to St. Joseph: For the Restless”), and other uneasy topics. Of particular note is “Travel Diary of Noah’s Wife,” which builds from her self-described “smug” position at the beginning of the poem to growing discomfort: mold developing, water and food stores becoming both scarce and less safe sustenance as they decay, and, finally, persistent guilt about those left behind: “aardvark, possum, child— / all whose lungs had once been sleek fish / rippling behind the coral of ribs.” The poems in this section reflect some version of this unease, that of the comparatively lucky against those less fortunate.

The final section, Rustle of Offerings, is the most personal in tone; “Why I Did Not Proceed with the Divorce” demonstrates Yu’s ability to build empathy throughout the progression of the poem, The touching final stanza demonstrates the intimacy of this section: “But mostly, because I slept in the guestroom / for six months / and you tapped on the door / each night, offering a glass of water.” The subjects of the poems in the final section are domestic, familial, everyday, moving away from the more overtly religious images in the earlier sections.

The Palm Leaf Manuscripts not only provide a thread across the book, but also serve to reinforce thematically the more specific situations of other poems to add an abstract element that elevates the concerns of the book to a more philosophical plane. These prose poems are announced as some kind of received genre or form: a myth, a fable, a proverb, a definition, and somewhat incongruously, a physics lesson. Many of the poems in this collection are startling and even disturbing, “Myth from the Palm-Leaf Manuscript” demonstrates the ways in which childhood memories are at once haunting and surreal:

Remember the woman who told you she found a dead cat on her deck, fur matted with August rain, how her husband nudged it onto cardboard with his loafer and dropped it over the fence into the neighbor’s azaleas? Make her you, you ten, her husband your father, before the divorce…

Make August February, the shoe a shovel. Let the shovel crack the frozen fur. Say you turned your face and saw your father’s shirts brittle on the clothesline, glazed with ice, and heard the shovel ring like the clapper of the church bell.

This concise story becomes a myth through the narrator trying to make sense of it: “This is the story the elders will tell when the wheat withers on the stalk and the firstborn swallow their tongues…this, the myth of the god of despair, who is the father of the god of attention.”

Yu illuminates the ways stories we tell ourselves provide comfort for our anxieties, regardless of the forms those stories take. How much different is a lie from a proverb or a prayer? All are designed to create a version of truth that suffices to take off the edge, or limit the damage, that comes of confronting the harder truths. Prayer Book of the Anxious is a well-crafted, serious meditation, constructed of powerful, haunting individual poems that add up to a memorable collection.

Kim Jacobs-Beck is Professor of English at the University of Cincinnati Clermont College. She is a second-year student in Miami University’s low-residency MFA program in poetry. She has a chapbook forthcoming from Wolfson Press. Two of her poems were recently nominated for Best of the Net, and can seen at Apple Valley Review, Rat’s Ass Review, Thank You for Swallowing, NILVX, Muddy River Poetry Review, and Bright Sleep.

Leave a Reply