Curb by Divya Victor review by Mandana Chaffa

Curb

Divya Victor

review by Mandana Chaffa

Nightboat Books, April 2021, 128 pages, $17.95

Divya Victor’s Curb explores immigration, identity, and the boundaries that keep us safe and those that keep us out. The preface poem, addressed to unknown recipient(s), reflects Victor’s linguistic precision and the contours of the subject she explores:

______________________ , since you asked:

yes; I am

afraid all

the time; all

the places are all

the same to me; all

of us are the same to all

of them; this is all

that matters; all

of us don’t matter at all.

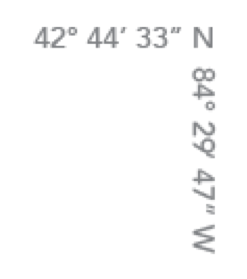

The lowercase acknowledgment—“yes; I am” —leads to a litany of “alls” and other repetitions that ultimately become a universal negation. The repeated “a” vowel suggests the vulnerability of an open mouth, an utterance that resembles an octet of sighs. There’s a visual distinction that’s in several of the pieces that follow. The upper right-hand corner of the page indicates a directional longitude and latitude that provides both a sense of location, literally (in the case of this preface poem, East Lansing, Michigan), and dislocation, thematically. (Victor mentions in the notes section its positional relation to Erica Baum’s well-known Dog Ears.)

The collection that follows provides the same blend of expanse and specificity. In addition to linguistic repetitions, Victor offers other longitudes and latitudes in several other poems, therefore enacting a physical grounding the way a gallery provides a space for visual art. It’s unsurprising that aspects of this collection were initially part of a clamshell artist’s book, as it still exhibits a strong three-dimensionality beyond the flatness of the page.

Victor is deeply interested in lines: written, physical, and figurative, and how they parallel and cross each other. It’s particularly meaningful in our climate, where there are lines that separate us economically, politically, and socially. She’s especially adept at noting the frequent ironies of such proximities. In “Hedges”:

at the consulate, the line

for birth certificates is the line

for death certificates

…………………..was the child born beyond a boundary?

…………………..was the boundary wrought in gunmetal & grain?

In only five lines, she investigates the narrow edge between life and death, between joy and grief, as well as the complications of shifting borders. She adds facets with the voice—in italics—of an authoritative, often heedless, inquisitor, and the implications of such questions. In “Lawn (Temperate)”:

…………………..Her name is small

talk here. It is inclement weather, a store going out of business,

an ongoing sale at the end of a season. It is one time something

happened & boy was it something. She slips into the Midwestern

apology, beer in hand: “There you go! You almost got it.”

These repetitions provide a glimpse of what it is to be in a marginalized group, shouldering the responsibility of educating the mainstream, with a forced smile that hides complicated emotions. There are public responses, and private answers, which reflect the true cost of leaving and being left.

Yet, this isn’t solely a collection of multifaceted wordplay and linguistic acrobatics. It’s also a showcase for Victor’s lyricism, here as she describes sharing her mother’s passport as a child:

until I was eleven, I slept

inside my mother’s passport

in that photograph, I wear the face

which drank the wet moons, horns & all. I have the eyes

of a deer crossing the pacific

two stitches on a single stave.

Later, she examines what immigrancy—or exile—is for these children, who are carted from location to location like accessories. When adults move by choice or force they have established roots and recollections they carry with them. What is the impact on a child without such memories, ties, or support? In “Milestones: A Theory of Marking/ Being Marked”:

How do we measure the tension & displacement of a body in

memories of having traversed, of having been moved, of having

been so utterly moveable? What is the force that can lift a child

into the air and throw her across the world?

Victor excavates and incorporate a range of languages and alphabets, without direct translation t (though there is an extensive notes section at the end). Words are never one thing in Victor’s world—in our world—and the more she examines them, as if she is a linguistic joule turning a word in bright light we see the variations, the frictions and subtle connections. Here she offers a haiku-like emotive watercolor of immigrancy, exile and the difficult road to acceptance: “how long, chetaa, / have we been here / before we arrived?”

The combination of journalistic excerpts, definitions, and poetic language interrogates the authoritativeness of traditional news reportage. Victor destabilizes readers’ expectations of truth—if indeed there is one truth—and encourages us to question what we hear, and sometimes heedlessly forget, without considering the damage, and the human impact. Victor pays specific attention to the deaths of four men—Balbir Singh Sodhi, Navroze Mody, Srinivas Kuchibhotla and Sunando Sen—in the South Asian community, offering this statement at the beginning of the collection:

This book was made to witness the following irreducible facts:

these men once lived; they loved; they were loved; the United

States of America is responsible for the force of feeling and

action that ended their lives.

Such hate crimes and other violence to people of color in word and deed is one of the subtexts of the collection as a whole. Yet in keeping with Victor’s clear-eyed descriptions, she also dissects prejudicial harms within the community and explores the conflict between skin shades even within communities of color.

When South Asians perform

anti-blackness as a form of a centuries-long aspiration to be

white, we erase and destroy an equally long history of coalition

between black and brown folk, and fail to acknowledge our

debt to civil rights processes that have guaranteed the relative

freedom of Desis in the United States.

In the sections “Hedges”—a title which brings to mind Frost’s “Before I built a wall I’d ask to know / What I was walling in or walling out,”— Victor might be responding that far from a bucolic New England setting “Our shared border is a fist / unfurling; a red flag.”

One language isn’t enough to capture Victor’s talent and story, yet conversely, her singular path has a resonance for every person. We all seek a place, a connection, and safety, in a wildly uncertain, evolving and devolving time. The more readers read these poems, the deeper they delve into the complexity of meaning. The chemical interaction between words, objects, and the alchemy creates a new element altogether. In a section from “Blood / Soil,” Victor writes:

The Law says: “If you press a stone

with your finger, the finger

is also pressed

by the stone”

Readers will feel like they have pressed and been pressed by this remarkable collection, which uses language as a weapon, as comfort, as demand, as identity, as gesture, and always, as connection.

Curb is akin to a modern jazz composition where the instruments—syntax, language, form, image—bend and break as contrast and amplification, and readers can appreciate the complexity of the work on a variety of levels.

first there was a line

& then there was a story

There are many lines—human, geographical, linguistic and physical—that Victor has woven together for this collection. The precision of these lines is brilliant, as are her artistic decisions to cross them verbally and visually, not for effect but as a way to reach the essence of a story, of a life, and of “civilizations” often intent upon curbing—often caging—people through thoughtless classifications. This collection is a powerful political act, yet it is first and foremost a poetic act, one that is not to be missed.

Mandana Chaffa is Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Nowruz Journal, a periodical of Persian arts and letters, and Editor and Senior Strategist at Chicago Review of Books. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in several anthologies, as well as in The Ploughshares blog, Chicago Review of Books, Colorado Review, TriQuarterly, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She serves on the board of The Flow Chart Foundation, and was named a 2021-2022 Emerging Critics Fellow by the National Book Critics Circle. Born in Tehran, Iran, she lives in New York.

12 October 2021

Leave a Reply