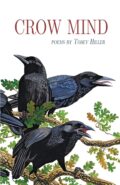

Review: Crow Mind by Tobey Hiller

review by Susan Nordmark

Crow Mind

by Tobey Hiller

Finishing Line Press, 2020

$14.99, 32 pp.

ISBN: 978-0963120717

Crow Mind is Tobey Hiller’s third poetry collection and her first in over ten years, and one that builds on her previous work while leaping into newly vivid color, relationship, and voice. Hiller has spent her writing life pursuing the ambivalence of humans in a world shaped not by us, and she has sought to parse a human place among those earthly forces and creatures that people of the modern west have rubricked “nature.” She rewrites the post-Enlightenment genre of natural history into a voyage of intimacy with the strange.

Hiller’s earlier work sometimes shared a Romantic sensibility with other California poets such as Joseph Stroud, Gary Young, and Gary Snyder. But over time she has shifted focus from those writers’ predominant focus on landscape to zeroing on animal life. She joins, too, Wyomingian Annie Proulx’s twenty-twenty lensing on the disjuncts between humans and the wild world. Using engagement with crows who visit her garden as her supertext, Hiller navigates beyond pop gee-whiz memes and gooey YouTubes of fubsy animals. Students of chimpanzee fieldworker Jane Goodall and raven zoologist Bernd Heinrich will resonate with the poet’s awe at these birds’ canny attentiveness. In Crow Mind she squirrels a track along how the mind does itself, often in a snappy, comedic voice suited to her trickster character:

……….“Sharp”

……….“…tripartite claws

……….swing a dinosaur swagger…

……….wit

……….as wide as wild…

……….More black cat ink

……….and strut.

……….He knows who goes there.

……….What’s what.”

Readers of Annie Dillard’s tale of an inchworm’s valiance will recognize a similar empathy.

The poet jogs a dialectic between Heinrich’s careful field observation on one hand, and Gretel Ehrlich’s evocation of the Greenlandic sublime on the other. She stretches and contracts, both wide-angling her longtime preoccupation with superhuman earth and sky energies and micro-focusing on specifics. She bridges ancient potencies–“sound makes the world”— of water, surf, rivers, trees redolent with green–with particular beings. This longing to ground is central to her vision of consciousness, human and not, alike.

The erotic mode arises in Strange Weathers and cracks through all her work to come.

In “inside the cypress forest” a pulse plumes from the land:

……….“Among these trees

……….Burning with an inside light

……….Like thighs

……….Or the inner chambers of a conch.”

“Fox & Moon” startles, a Pleistocene magic-erotic agon:

……….“He bays at her,

……….sharp teeth pricking night.

……….Tries to lick her

……….with his long tongue.

……….She drips light, drenches him

……….with boneshadow,

……….prickles his fur into

……….silver thistles &

……….pulls his ears flat with longing

……….pouring howlmouth moonwounds

……….into his skull.”

The poet shifts to a woman’s voice, slow and tender, in “The delicacy in men’s bodies”:

……….“hidden behind muscle and gut

……….the large breastplate of chest

……….and swelled armor of the belly

……….suddenly appears…

……….women can see whether there is that lazy music

……….in a man’s resting empty hands.”

Crow Mind sails this stream of desire in the crows Hiller lives among. Of a female bird, she writes in “She Bathes”:

…………………………“To me

……….she seems languorous

……….taking long and

……….slow, eros in

……….an interval away

……….from all clutter…

……….you might say

……….pleasure, you might

……….say

……….self.”

She sees too the male crow, flooded with passion, in “How Crow Became Legion”:

……….“His heart’s as red and pulsing

……….with all the heart’s four and twenty chariots of desire

……….as yours and mine.”

The poet enraptured. Crow’s backward-glancing flirtation turns coy pas de deux that flares across distance. Inveterate attention to the lover’s smallest gestures fuses into literary romance in rhapsody at the lover’s sneaky grace. Hiller rewrites the paean to the elusive lover in “Crow knows”:

……….“He shows

……….a black box fox-like glance to me,

……….dives into

……….sky, the large

……….goodbye of caw

……….and go…

……….and all that’s

……….in between my here,

……….his there…

……….whose mineral and liquid names

……….I do not know…

……….Crow

……….Rows up into sky and disappears

……….into…

……….his memory

……….of me…”

Likewise Hiller herself wanders, returns, is left bereft.

……….“I went away.

……….I came back.

……….Three days. Four.

……….I have not seen them…

……….Where are they?…

……….Who

……….will speak my name

……….when I am gone?”

Many cultures have engaged the trope of the woman who marries a bear, the man lusting for a woman who is part bird, the woman who makes love with a seal. Sex itself is chaotic, violating, and these tryst narratives generally end as tragedy.

Contemporary poets have also played this therianthropic game, though not often via the image of coupling. Ted Hughes’ stab at it imagined a Platonic form of Crow as predatory, murderous, a projection of that poet’s own bloodshot heart. Hiller’s longing to delve into animal spirit comes not from Hughes’ unowned shadow, but from considering ones-of-a-kind. Still, readers of Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’ animal journey intermezzos in Reindeer Moon will be reminded of both writers’ struggles to submerge into creatures they cannot really know.

An uncollected piece, “Izmir Story,” situates experience in negation and disorientation. Hiller uses fragments–“without knowledge,” “strange room,” “unknown name”—as well as space and movement across the page, to do the work of confusion, of gravity loss. She acknowledges planetary powers as literary personae, and ones more adventurous than any human. Wind and ocean dwarf human makings, swirling carelessly about us. We are latecomers to this planet, one we, almost translucent in agency, at best inhabit in those fortunate moments we are overlooked by the gods. Here Hiller hints at Buddhist “no self,” recalling Merwin’s late poems—humanity as a cloud of transparent medusas blown through the pelagic.

Like Goodall, Hiller is an ancestrally European writer settled in non-European space, but while Goodall plunked herself in African rain forest imagined as timeless pastoral—people cropped out of the picture plane–Hiller’s homed herself in California firestorm country. It’s an Anthropocene landscape that fast-forwards into a phalanx of flame throwers half the year, incinerating animal and human alike. Fire asserts godhood.

Still, life organizes. Throughout her work Hiller dances with one foot in text-making and epic-singing, asserting language and story as central to consciousness sculpting itself. From Aqueduct:

……….“into”:

…………………………“glowing seaward

…………………………edge words

……….ledge of what I can–knot of what

……….thicket ’tween us

…………………………glossaries of rain

…………………………the tongue’s more than

……….single

……….wordage——glowing seaward…

……….her fluency

………………..of rivers”

To make language is to think. To think is to make. “His Philosophy” workshops the crows together with the poet herself, fellow bricoleurs, with the glint-eyed birds more easy-come-easy-go. She compares their famous habit of collecting bright ephemera with the poet’s own shred-piled torn lines:

……….“…backs of envelopes, scraps of post-it, bits of paper, scribbles…

……….Chitbits

……….stuck in paper haystacks and desk tide scruffle…

……….Crow knows this…

……….if he misses that delectable mouse…

……….he moves on.”

Though Hiller throws asides to myth and philosophy, no reader has to glue herself to Google to follow her through-line.

These poems weave Hiller into the American conversation about nature, from the Hudson River School to John Muir, Emily Dickinson to Barry Lopez and others. That narrative is one of care and longing, a plea to glimpse what humans are violently causing to vanish.

Crow Mind is a trek through a North American garden, one where people don’t need to wait for Vulcan First Contact Day because aliens have always been here. And it’s a love story in which, as in most romances, the beloved remains just out of reach.

Susan Nordmark‘s fiction, essays and poetry have appeared in New World Writing, Heavy Feather Review, Long Island Literary Journal, Sin Fronteras: Writers Without Borders, Entropy, Draft: The Journal of Process, Porter Gulch Review, and elsewhere. Her work was selected for Peacock Journal Anthology 2017. She lives in Oakland, California.

Interesting how the poet switches voices, and definitely like that she poses questions throughout. Nice review, Susan. Made me interested enough to research the poet and read some poems

insightful depiction of the connecting links between animal-nature-human spheres.

And reading here I recall the nature writing of Helen Macdonald (“H Is for Hawk”) and Bernd Heinrich (“Mind of the Raven”). Most especially the rapturous novella “The Bear” by Marian Engle and the animal sculptures of Mary Engle (see the Marcia Wood Gallery). The reviewer herself uses language that evokes Tobey Hiller’s words and thoughts. Is this what happens when we read what we love? This can’t just be me. Lots of hybrid people here. I thank you all.