Review: The Clearing by Allison Adair

reviewed by Mandana Chaffa

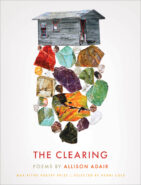

The Clearing

Allison Adair

Milkweed Press, June 2020.

$22.00; 88 pp.

ISBN: 978-1571315144

“What if this time instead of crumbs the girl drops / teeth, her own, what else does she have”? So starts the title poem and prologue of Allison Adair’s The Clearing—winner of the Max Ritvo Poetry Prize—setting the stage for the lyrical stories to come. These are no fairy tales with happily-ever-afters, nor with clear-cut villains. Rather, the players in these folk narratives are marked by time, eroded by the elements, distilled down to their flawed, human essence, both haunted and haunting.

Whether Adair is focusing on the complexity of relationships or the expansiveness of our natural world, there’s a timeless depth and rooting in these explorations. Her vision is kaleidoscopic, in the way she manipulates phrases and images, remaking them into dazzling new impressions, as in these excerpts from “First Plow at Red Mountain Pass”:

……..How the skin

……..of a flat blue sky pulls taut, from

……..nowhere, matte, low, bowing

……..like a cosmic hammock

……..wet with stars.

……..[. . .]

……..spilling out a crowd

……..of white consonants, an argument

……..against the darkening afternoon.

……..We depend on things to fall.

These poems should be read aloud to fully experience the delights of tasting and lingering over such heady vowels and consonants. Adair’s depictions are stunning: from fireflies vomiting daylight to “Explosions of promiscuity: coral peonies, lady slipper, / gape-mouth jewelweed” to a place where “In the dry / collarbone of a mountain, sentences end / with a still body.”

There’s a remarkable sense of geography and history in this collection. The span of nature—in millennia—juxtaposed against the space of bodies, the vulnerable biologies of people, whose lifespans resemble those fireflies in comparison. Adair has the rare ability to draw upon evocative memories of simpler times, for people and this planet without falling into the trap of treacly nostalgia, as she does in “Fable”:

……..Reader, every year we get this moment wrong. Do we

……..know each other, our own bodies, our annual flex and bloom?

……..When you come to me, finally, overgrown, distended

……..with broad green leaves, will I remember where to lay

……..my hands, how to look away as longing, as lure?

and this whisper of an etching of memory’s longing from “Western Slope”:

…………….</h4>(But—before I go—wasn’t it us for a while? Weren’t we the neon

…………….</h4>kicking in the light? Tell me you remember the waves

………………………………….</h4></h4></h4></h4>bathing our necks, our small ears?)

Adair populates her poems with shifting pronouns, giving voice to the elements, inanimate objects, and a range of individuals who yearn, who are disappointed, who strive for a happiness that may be unattainable. In the world of her poems, every entity has a story to tell, from the witness to the violent fist, even the very walls:

……..I think the knuckles in the wall will break

……..through tonight. The hollows hang there,

……..indentations his closed hand left once, and again,

……..shadows of instinct. People now don’t speak

……..this language of apology, of small desperate joints

……..asking the sheetrock to stop closing in on a man.

Adair’s specificity of language offers readers the sheer joy of unexpected words, those that crackle as you rip off their cellophane wrappers. There’s a dreaminess in these poems, a lusciousness of narrative, though her masterful control ensures there’s no risk of being abandoned in the verdant foliage of such language:

……..The world, first, is local

……..music, then we are taught bellows

……..from harp, from shovel hitting ground.

……..[. . .]

……..Already you know the notes

……..of collapse: wind slab, point release,

……..cornice fall. Under your jacket,

……..an avalanche beacon ticks

……..like a human heart.

Some of the most memorable works are centered on those who work the earth, who break down the ground and are broken down in return. “The Big Thinkers,” one of several prose poems, is a masterpiece, a mother lode of cinematic lyricism. With the expansive “we,” Adair is speaking of and for the silent and the silenced, those surrounded by land rather than oceans. What can grow here, seeded by rusted machines, the metallic scents of blood spilled, of lost dreams?

……..I’ll say it plain. We’re not from there. Out west things are big under a big

……..sky with clouds you have to imagine hard it’s that blue. Blue the way people on

……..coasts insist water should be because it once was, somewhere we’ve never been.

……..The color of nineteenth-century dreams, elemental and distinct, as if each object

……..in the world had just emerged dripping from a vat of pure pigment.

……..Unambiguous. Red earth, green trees, white stars, and under it all: gold. Gold

……..the color of a man in a new suit, walking around town with no one to answer

……..to. Listen. I’m telling you we don’t know that man.

……..[. . .]

……..Fat bankrolls swelling in an imaginary pocket

……..is them while our people just do, slowly, in the dark low mines of Bethlehem,

……..Centralia, wiping coughs away with a thick sleeve, knocking at the walls of

……..loose dirt with an axe the size of a cocktail spear, chipping away at the dark

……..rock till the vein shines, but only slightly and if you have your headlamp, you

……..see our scale isn’t big, we’re the thin pink lung of a winded canary. . .

There are moments this distinctive on every page, and beyond the vivid imagery of the natural world, Adair—in an eminently relatable manner—exhibits tremendous empathy for those who may have more endings than beginnings left to them. She is particularly adept at depicting the frictions of the aging process, indelibly in “As If the World Might Hold Another”:

……..We approach

……..middle age as undiscovered country when

……..really it’s the same old alley, the bowling pin

……..that wobbles like a drunk but won’t go down.

……..[. . .]

……..The nursery walls

……..hang, still painted a neutral blue—robin’s egg,

……..as if the world might hold another spring. I’d beg

……..to be a nest again, one more time, but how

……..to fasten this mangle of fresh grass to this dry bough?

It’s difficult to believe that The Clearing is Allison Adair’s first full collection of poems. Her once-upon-a-times are generational oral histories, from the Civil War to present day. They will endure, even as the land and these people endure, despite the violence done to it and them, despite the attempts to silence them directly or by neglect. Adair speaks for and through them, allowing their rugged, dented beauty to shine through in exceptional fashion. This assured, layered, altogether extraordinary debut collection will linger in readers’ minds long after the first reading.

Mandana Chaffa is the founder and editor-in-chief of Nowruz Journal, a periodical of Persian arts and letters that will launch in spring 2021. Her essay “1,916 Days” is in My Shadow is My Skin: Voices from the Iranian Diaspora (University of Texas Press 2020) and her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in the Ploughshares blog, Rain Taxi, The Chicago Review of Books, Split Lip Magazine, The Adroit Journal, The Rumpus, Jacket2 and elsewhere. Born in Tehran, Iran, Mandana lives in New York.

Leave a Reply