Review: The Carrying by Ada Limón

Review by Gillian Neimark

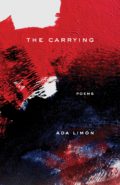

The Carrying

Poems by Ada Limón

Milkweed Editions, August 2018

$22.00, 95 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1571315120

Ada Limón’s fifth book of poetry, The Carrying, opens with an intriguing, brief poem—like an epigraph or riddle that isn’t quite clear until one has read the whole book. Simply called, “A Name,” it describes Eve, who “walked among the animals and named them.” Did she ever, the speaker wonders, want them to speak back? Did she whisper to them, “Name me, name me.”

This book is rich with naming, discovery, and rediscovery of self and world. Even more so, being named back propels every one of these poems. As a reader I often feel that Ada Limón is speaking directly to me, wanting me to feel her deeply. These are richly autobiographical poems. If I knew nothing of the poet before I opened the book, I would leave it knowing that she’s deeply in love with her husband, moved to Kentucky to be with him, attends horse races, is trying to get pregnant, and endures weeks or months-long attacks of vertigo. That she’s crazy about gardening. That she suffers ongoing problems from a childhood spinal curvature. That the love between Limón and her artist mother is deep and sustaining.

I come away from The Carrying with the comforting feeling the poet is my real life friend, and that if and when we ever meet, we’ll simply take up the thread of conversations she and I have been having on the page. She achieves this intimacy through her extraordinary and fearless ability to marry colloquial language – even consciously clichéd, threadbare everyday speech – with disciplined and gorgeous linguistic flight. This makes for a poetics that veers seamlessly from everyday intimacy to the deep and abiding and eternal. Just walking her dog, who runs like so many dogs “straight toward pickup trucks” in “The Leash” brings her to an enormous conjecture: “Perhaps we are always hurtling our body towards / the thing that will obliterate us, begging for love / from the speeding passage of time.” The leap is huge, but she has already seduced us with her customary and easily confiding tone, so we leap with her.

It’s watching her do this, in poem after poem, that’s so interesting. She is perfectly capable of rendering the familiar new—“we take out the trash, the rolling containers a song of suburban thunder” she writes in “Dead Stars”; in another poem called “Dandelion Insomnia,” bees are “tipsy, sun drunk /and heavy with thick knitted leg warmers/of pollen.” But just as often, she deliberately chooses not to. Amazingly, she can get away with lines like “eyes still swollen shut with sleep” (from “American Pharaoh”), “raging infection” (from “Bust”), “down the drain” (from “I’m Sure About Magic”), “his face closes like a fist” (from “On A Lamp Post Long Ago”). Those plump, overused phrases are part of her (and our) lived experience, as worthy of inclusion as lawnmowers, red mailboxes and barking dogs; or stars, death, and magic. She intentionally sweeps it all into her work.

Take one of my favorites from this volume, “Dandelion Insomnia,” in which the most ordinary, homely flower—so often called a weed—reveals the remarkable ability of all life to remake “the toughest self.” The speaker begins with an admission:

I was up all night again so today’s

yellow hours seem strange and hallucinogenic.

The neighborhood is lousy with mowers, crazy

dogs, and people mending what winter ruined.

This is signature Limón, lulling us into a comfortable intimacy with a confession and half-complaint about a sleepless night, lawnmowers and barking dogs—and then with the same confiding frankness, she spools into the astonishing capacity life has to mend what has been ruined by real and metaphorical winters. Just like dandelions sprouting on her neighbor’s freshly mowed lawn:

It must bug some folks,

a flower so tricky it can reproduce asexually,

making perfect identical selves, bam, another me

bam, another me.

We are all the tenacious dandelion, mowed down by winter or sleepless nights, by any misfortune, but, as the poem concludes, “remaking the toughest self while everyone / else is asleep.”

“Notes on the Below,” where she speaks to Mammoth Cave National Park as if it were a wise elder, a dark deity, is an unforgettable hymn and supplication.

Tell me—humongous cavern, tell me, wet limestone, sandstone

caprock,

bat-wing, sightless translucent cave shrimp

this endless plummet into more of the unknown

tell me how one keeps secrets for so long.

The cave, untouched by light, in fact, not needing light at all, absorbs into itself endless dark and time. It’s made of “400 miles of interlocking caves that lead / only to more of you.” It’s a silent necromancer of inwardness and renunciation, “Ruler of the Underlying,” able to speak to “both the dead and the living” to what’s “underneath asking for nothing.” In contrast, she places her small and real, hungry self before it: “All my life, I’ve lived above ground…I’ve been the one who has craved and craved until I could not see / beyond my own greed. There’s a whole nation of us.” The cave seems to offer endless openings into contemplative prayer. It reminds me of the lessons of The Cloud of Unknowing, where one rests in God, and there is an enfolding, mysterious darkness to that God. Yet even to the last line, Limón knows she is unlike this cave-deity-dark-enfolding-God. “I am at the mouth of the cave. I am willing to crawl.” We want to learn. But even when we seek God-ness in a cave, we are still at its mouth, desiring.

The miracle of naming and being named, the fall from grace into knowing this exquisite world filled with “fiddler crab, fallow deer” (from “A Name”), the never-stanched desire to see and be seen, feel and be felt, call and be called—that is this poet-as-Eve’s mission. Every rustle and roar of nature, grasses, horses, ravens, stray cats, and dying raccoons—all of our world transports, troubles and calls to her. She walks among us as if she were that original woman, calling the things of the world into being. As you read, you can almost feel her turning, and whispering to you, “Name me, name me, too.”

Gillian (Jill) Neimark is an author of adult and children’s fiction and nonfiction. A former contributing editor at Discover Magazine, she has also written for Scientific American, Science, Nautilus, Aeon, The New York Times, NPR, Quartz, and Psychology Today. Her novel, Bloodsong, was published in hardcover in 1993 and paperback in 1994, was a BOMC selection, translated into Italian, German and Hebrew, and optioned for film. She is the author of three picture books and two middle-grade novels, and her poetry has been published in the Cimmarron Review, Borderlands, the Massachusetts Review, and the Columbia Review.

Hello Aida, I’m looking forward to your creative writing reading series on October 9, 2019. I enjoyed reading the Dandelion insomnia poem.