Review: I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood by Tiana Clark

Reviewed by Leonora Simonovis

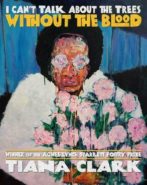

I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood

Poems by Tiana Clark

University of Pittsburgh Press, September 2018

$17.00; 96 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0822965589

The late Toni Morrison claimed that “in this country American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate.” Many African American writers navigate this hyphenated zone, exploring a severed identity that fluctuates between a motherland—Africa—and the space currently inhabited. Tiana Clark’s stunning poetry collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood, interrogates the past and its continued impact on the present from the intersections of race and gender, and the consequences of discriminatory practices on African American communities.

Clark’s speaker, of mixed race, examines her conflicting identities—Black and white—as well as her role as a woman whose body has been—and still is—a site that represents intergenerational violence. The speaker evokes a larger body of literary and cultural influences that have consistently challenged the systematic erasure of African Americans in the United States. Thus, the private and the public interconnect in the juxtaposition of personal narratives and historical research.

I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood is divided into three sections, each of them named after part of the title—“I Can’t Talk,” “About the Trees,” “Without the Blood.” The first section explores the historical divide between whites and Blacks in United States history, and what it means to be silenced and censored. The second honors the strong presence and influence of African American artists, including Phyllis Wheatley, Lucille Clifton, and Nina Simone. The third examines, literally and metaphorically, the significance of blood. For example, the poem “First Blood” critiques a culture that reveres blood that is shed in war and simultaneously shames women for menstruation.

One poem that examines the role of history and how it is embodied by the speaker, is “Soil Horizon,” from the first part of the collection. When the mother-in-law asks to have a family portrait taken at Carnton Plantation, she fails to understand the implications this might have for the speaker, “We could redeem the land with our picture.” She explains that her sons played on the plantation grounds as kids, and that “There are so many fun places to shoot,” a reference to the family portrait but also to the violence enacted upon slaves. The poem turns ironic as the speaker reflects on her role within the family and the commodification of historical sites of Black suffering by non-Black people—in this case, by members of her own family:

How do we stand on the dead and smile? I carry so many black souls

in my skin, sometimes I swear it vibrates, like a tuning fork when struck.

The speaker recalls how important this particular plantation was, because it was turned into a field hospital during the Battle of Franklin. However, according to a brochure she reads, the site is now,

sold for summer weddings with mint

juleps in sweating silver cups…

The poem weaves present and past together, so that the camera shutter is “like a tiny guillotine,” and the speaker’s hair parallels the soil, as a light drizzle falls and her curls spring up. She imagines the water seeping down “to the antebellum base, the bedrock of Southern amnesia,” while in the background the mother-in-law’s voice drones, “Can’t we just let the past be the past?” The poem ends: “In the portrait, my husband is holding my hand—his hand that dug for bullets as a boy.”

The dynamics between the speaker and her own family can be seen as a microcosm of the whole nation, calling attention to the systematic erasure of Black people and Black culture. This collection challenges the reader to think beyond the boundaries of the history that has been taught in schools and highlights the narratives that have obscured and varnished race relations in the United States.

The last poem in the book, “How to Find the Center of a Circle,” evokes the first time the speaker is called a “nigger” at school, connecting this particular event to the branding of slaves, intergenerational trauma, and the complicity of a society that refuses to see the consequences of its indifference and inaction,

Speaker and reader are transported to the past while being made aware of its connection to the present. Clark’s poems question a society that relies on artists of color to carry the weight of atonement on their shoulders. Thus, the question of why the past cannot stay in the past answers itself in this haunting and beautiful collection.

Leonora Simonovis is a Professor of Latin American and Caribbean literature at the University of San Diego and an MFA candidate at Antioch University. Her chapbook manuscript, Waiting for a Ripe Mango, was a finalist for the Tupelo Press Snowbound Chapbook Contest (2019) and is forthcoming from Skull & Wind Press. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming from The Rumpus, Arkansas International, Inverted Syntax, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and Kenyon Review blog, among others. Leonora is a contributing editor for Drizzle Review, where she highlights the works of underrepresented authors. She lives with her family in San Diego, CA.

Leave a Reply