Review: The Accidental by Gina Franco

Reviewed by Shannon K. Winston

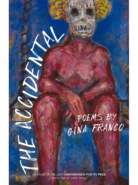

The Accidental

poems by Gina Franco

The University of Arkansas Press, October 2019.

$16.95; 88 pp.

ISBN: 978-1682261057

Gina Franco’s The Accidental is stunning, deft, and ambitious—all of which Deborah Paredez and Carmen Giménez Smith capture in their assertion that “Gina Franco’s poems are bone and bark and bough; they are spirit and sangre and sutures for the wounds that dwell along the geographical and metaphysical space of the borderlands” (Preface, vii). As Paredez and Smith suggest, The Accidental is far-reaching and capacious. It broaches metaphysical questions of the self and religion, while also giving voice to forgotten histories, particularly Latinx histories of violence at the U.S. border. Franco weaves numerous illusions into her work, including to G.W. F. Hegel, Simone Weil, Juan Rulfo, and John Ashbury, and she navigates this material with grace and nuance. Her poems demand to be read and reread. They require patience. Readers must slow down in order to appreciate their density and complexity. Yet, Franco’s poems are far from esoteric. They are mysterious and mystical, but not obscure. They contain so much—so many allusions, histories, and emotional stakes—that they cannot help but invite a wide range of readers into their folds. Indeed, The Accidental hinges on multiple, overlapping perspectives. Each poem challenges readers to see the world differently, as this sentence from the prose poem, “Our Mother of Rivers Is Made Our Perpetual Hanging Garden,” renders explicit: “And here was the eye, suspending what it saw in what it still sees, where there was nothing left to see.” Franco asks readers to interrogate the limits of their sight, to unknow what they take for granted, and to see the world as marvelous again.

Vision and technologies of sight are central to The Accidental. Where is the boundary between the visible and the invisible? How much of our world can we see and truly know? How can we make sense of vision (in the perceptual sense) and visions (in the religious sense)? These are just a few questions The Accidental broaches by way of references to vision and to technologies of sight. In the poem “The Spirit Is Bone,” for instance, there is a lone window through which the speaker glimpses a fragmented external world. The speaker can only see “the room’s partial tree, leaf-/less yet: partial/stone-/hinged clouds.” The abrupt line breaks mirror a partial vision, whereby both the speaker and reader search for “the piece that goes missing, that remains.” Other poems invoke technologies of sight, especially the camera. In “Annunciation of the Self-Enclosed God,” for example, the poem makes reference to a “wide-angle lens” and “a monochrome/snapshot” in looking for “the beloved”—a term that conjures both God and a lover waiting on a front porch.

One extraordinary strength of The Accidental is its ability to bridge the abstract and material worlds. The eponymous second section, for example, comprises a series of prose poems meditating on the soul. Franco estranges common conceptions of the soul by depicting it as embodied: “it paused to smell the water warming on the smooth cement” and “felt the cool sweet skin of leaves on its new lips.” These moments depict the soul as rooted in the material world as it watches the father on the lawn and soaks up the natural world. Franco refers to the father (italics mine) with a lower case “f,” a typographical choice that illustrates the complexity and care with which the poet incorporates multiplicity into her work. For here, of course, the definite article the father recalls the Father in a religious sense, but the lower case “f,” along with the quotidian-like nature of these moments, also conjure a family scene in which one might have watched one’s father in the yard one summer afternoon. In this way, the spiritual world becomes familiar and accessible, and the everyday is transformed into the sacred.

One of the ways in which Franco encourages this multi-faceted interpretation of her work is through word play. The poems continually manipulate language in order to showcase the ways in which shifting language engenders shifting narratives. The poem “Refrain,” for example, conjures dragonflies. The speaker begins: “The dragonflies again; the last time seeing them/skim the river so close.” The speaker’s awe at the natural world becomes animated by the end of the poem when “the dragon flies again.” This repetition with a difference—in which dragonflies morphs into dragon flies—encapsulates the ever-shifting role of language and the conscious and unconscious ways in which meaning is made. A change in a letter or an added blank space opens up new imaginative possibilities.

Just as Franco explores the borders of sight and language, so does she probe geographical and historical borders. The collection’s first poem, “Otherwise All Would be God,” is dedicated to Carmen Rios, a flood victim in Del Rio, Texas. The poem, “America,” is for Maribel Alejandra Cortinas Segura, who was stabbed and died in the same town in 2009. These poems make the reader dwell in discomfort and see, for example, that “[s]omeone has left another body in the sand, human, sallow, hornless as a hunted animal, naked and socket-eyed.” With exacting and haunting images, Franco bears witness to a history of racial and gendered inequality. The image of a tree is repeated in several poems—a repetition that pays witness to the tree in near which Rios’s body was found and, by extension, to her life and death. But the tree not only conjures up violence; it also serves as a reminder that violence is never far away—a theme explicitly explored in the poem “What Shall I Cry?” Rather than a geographical demarcation, the border in this poem is a spatial one: the walls of the speaker’s apartment are all that separate her from her neighbor who is being abused. The poem begins: “sobbing, hers, late and in the dark, while I lie/ awake and listen for a sign of something more.”

What does it mean to witness the world in all of its grief and beauty? How does one make sense of injustice and pay homage to forgotten histories while still reveling in the worldly and in the divine? Franco does not shy away from these large questions, but she approaches each poem (and implicit question within each poem) with humility and a keen eye. Every one of The Accidental’s poems might be likened to a discovery—of the self, of others, and of all that binds us to one another.

Shannon K. Winston‘s poems have or will appear in RHINO, The Citron Review, Dialogist, The Los Angeles Review, and Crab Orchard Review, among others. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and several times for the Best of the Net. She earned her MFA at Warren Wilson College. Find her here: https://shannonkwinston.com/

Gina Franco’s poetry requires that I read…and reread..then set a time to ponder on what I have read. There seems to be a thin line that divides beauty and sorrow. I am in awe of Franco’s heart felt honesty.