Book Reviews: April 2013

You Good Thing, Poems by Dara Wier

Out Across the Nowhere, Stories by Amy Willoughby-Burle

You: An Anthology of Essays Devoted to the Second Person, Kim Dana Kupperman, with Heather G. Simon and James M. Chesbro, Editors

Holding Silvan: A Brief Life, Memoir by Monica Wesolowska

fff

You Good Thing

You Good Thing

Poems by Dara Wier

Wave Books, 2013

ISBN-13: 978-1933517674

$16.00; 64pp.

Reviewed by Wesley Rothman

Dara Wier’s You Good Thing wrestles down language, or is entangled, ensnared, enraptured by it. She warps syntax and thought, and maybe emotion, into postures that at first feel impossible. Wier has toyed with her poetic body to an incredible extent, and You Good Thing serves as an interactive exhibition of what it means to make poems, most importantly as a social human being. This is nothing like overwrought, humanless, machine poetry. It is the mad science of language.

Certainly, the sonnet is the guise for each of these poems, and the form functions much like a consistently sized and shaped canvas for a painting exhibition. What the artist does differently with a seemingly uniform structure becomes a reader’s primary concern. And Wier does not ease up or hold back from linguistic and contemplative complexity, from meaningful acrobatics.

Readers are met with a geometric sketch by Fernando Pessoa and the collection’s epigraph “by the longest possible route.” We follow this longest route, without section breaks and without much clear guidance (or perhaps with complete guidance, unbeknownst to us) from the speaker, the poet, the progression of these pieces. It is clear, however, that pronouns dominate these poems. In nearly every instance there is a we, an I, a you. Relations never fully reveal themselves, but prove pivotal to the goings on of each poem. We begin. “Not a Verbal Equivalent” tows us into the book with its first word and line (my italics):

You said one thing as a way of not saying something else

And, as first in the series, this poem establishes the collection’s perpetual concern with the nature of language, its abilities and inabilities to interpret and/or communicate thought and feeling.

Throughout the book, and often within a single poem, the reader can sense the speaker’s pendulum-like shift from complete faith in language to a very serious skepticism of its capacity. Language swings from clear, confident, and straightforward

We hold these birds in our fretful keeping

(from “Stainless Steel Spiders”)

through hazy, just-out-of-reach tangibility

Why do you believe? When a perfectly sane person, you, Asks me today, has a supernatural experience ever had you?

(from “You Are Our 3rd Destination and Our 9th Destiny”)

to grasping, urgent uncertainty

We pass by there, look here, what’s this my fingers

Are saying to my thumb, you know those famous silent

Skies, hear a twisted engine’s contortions discharging

Ignition ignition

(from “Without You”).

Wier perhaps never loses faith in language, but tries to find a limit to its uses, grabs the perceived boundaries of it and pulls it like Stretch Armstrong over many miles, maybe full continents. The poet drives some kind of serious and important skepticism, I think, not only of language, but of perception and the human place in space and time.

Wier gives us a book. While reading it we pass time while in space. We take the book with us, set it down with ourselves on the train, in a bed, with a couch. Throughout the book people are moving, time is passing, and those people are affecting time and the space around them. We are given the collection title in “Oblivious Conclusion” after the speaker says,

I suspect

It might be a result of times we picked up the river and put it down

Where no river has ever been. I wonder. If in a hundred years you’ll want

To move the river again[…]

You swiped the river and pounded it on rocks. You good thing.

For Wier this urge to move, to swipe and pound, is a good thing. The person with the urge is a good thing. And the river swipes and pounds, moves through time and space to the very last lines of the collection (and of course beyond it):

You are racing or flying so your velocities sway us

Into all keening wavering telegraphic of broken into

Thundering so go you go on as you were into the hills

Into this river leaving us with little to do with our hands.

To the last, language is sculpted; faith of many kinds bent; time, space, and their pronouns remain in question. Wier’s poems pound certitude over a rock, crack out the juices inside.

Out Across the Nowhere

Out Across the Nowhere

Stories by Amy Willoughby-Burle

Press 53, 2012

ISBN: 978-1935708605

$12.95; 93pp.

Reviewed by Natalie Sypolt

In “Out Across the Nowhere,” the title story from this slim volume of stories, the first from Amy Willoughby-Burle, the young narrator says of his parents, “We don’t hold their helplessness against them. They didn’t mean for all this to happen. They meant to look for us when we got lost. We made our own map instead.” Willoughby-Burle’s fictional world is populated by flawed characters, parents and children and friends, all teetering on the their unique edges—of despair, failure, desperation—but in every story lives the hope that no one will ever be completely lost.

People often make bad decisions, or find themselves in undesirable situations without being quite sure how they got there. The characters in Out Across the Nowhere are no different; however, honesty and humanity lie at the heart of this collection, which makes it difficult to judge the neglectful parents, flighty college students, and errant friends too harshly. Willoughby-Burley’s characters do not have easy lives, and are often in need of compassion; luckily, in the hands of this capable writer, they almost always get the opportunity for redemption.

This theme of struggle and forgiveness is evident in “Hungry,” one of the strongest stories in the collection. Here, Willoughby-Burle confronts poverty, an issue that is often overlooked in fiction because it is not “sexy” or “exciting,” but is at the forefront in the lives of many American families, and certainly worthy of closer investigation. The mother in this story “tries not to go on food stamps, but pride gives way easy to a child’s aching stomach.” She struggles to keep the lights on, to pay the rent, to pretend to be one of the women who buy “fresh fruit and good meat and deli slices of cheese to fill whole wheat, all natural, bakery fresh bread for their well dressed children’s lunch snacks.” When her work hours are reduced, the landlord kicks them out, and she’s tired of the fear that comes with sleeping in shelters. She takes her children to Social Services, ready to turn them in like “a litter of kittens.” Is this a selfish or a selfless act on the mother’s part? When ultimately the mother cannot leave the children and takes them away, should we cheer, or judge the woman for not doing what might have been in the best interest of these children? Through deft prose and a light touch, Willoughby-Burle reminds us that there is no easy answer when families are in crisis.

While the situations presented in this collection may often be difficult or unhappy, these are not characters asking for pity or sympathy, as they might be in the hands of a less-skilled writer. Willoughby-Burle treats her characters with respect and kindness. She does not preach or push, but simply presents a relatable story, and allows the readers to find their own way.

“Into the Burn,” the last story of the collection, ends with these lines: “Something new is happening. Something old is floating away.” With this piece, as with most of the stories in Out Across the Nowhere, there is the feeling that with compassion and understanding, human flaws can be forgiven, and for each of these struggling children, parents, and friends, there is the possibility of a different future; the possibility of hope.

You: An Anthology of Essays Devoted to the Second Person

You: An Anthology of Essays Devoted to the Second Person

Kim Dana Kupperman, with Heather G. Simon and James M. Chesbro, Editors

Welcome Table Press

ISBN-13: 978-0988592605

$20.00; 206pp.

Reviewed by Joe Ponepinto

The rewards and pitfalls of employing the second person point of view make it a risky alternative to traditional first and third person approaches for most writers. But that in turn makes the idea of including about forty such essays in an anthology one of the more intriguing publishing ventures this year.

At their best, second person essays (and stories) provide a powerful technique for confessionals, allowing the author to approach the challenge of self-examination by deflecting faults and guilt onto an unnamed other, as Joan Connor does superbly in “Change of Life.” The most successful efforts in this anthology also experiment with the epistolary form, such as Sonja Livingston’s “The Ghetto Girls’ Guide to Dating and Romance.” And there are essays that subtly alter the common imperative form of second-person writing into a sympathetic and coercive form of instruction, resembling more a conscience than a command: Sarah Stromeyer’s “Merce on the Page,” and Linda Underhill’s “Sound Effects.”

At their not-so-best, however, attempts at the second person illustrate failings that contribute to the form’s lack of popularity—a demanding, smug, sometimes haughty tone that can be difficult to take seriously, or extreme self-indulgence in the name of soul-baring—and unfortunately for this alphabetically arranged volume several of the early essays exemplify these traits. “Questionnaire for My Grandfather,” comes across as something more like an Inquisition. The imperative of the second person can also be reduced to finger-wagging lecturing, particularly when the effort is directed at a child (“If You Should Want Flowers for Your Table.”)

The gamble taken when presenting so much of this rare form is appreciated and even applauded, although this reviewer would have preferred fewer pieces about childhood or pregnancy or the usual problematic relationships one sees in far too many literary journals and which occasionally cross the line into the sentimental. Interestingly, the final essay in this book, Rachel Yoder’s “Some Really Disgusting Essays About Love,” takes issue with that aesthetic.

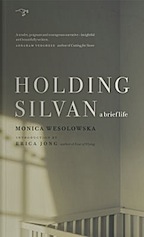

Holding Silvan: A Brief Life

Holding Silvan: A Brief Life

Memoir by Monica Wesolowska

Hawthorne Books & Literary Arts, 2013

ISBN: 978-09860000713

$16.95; 202 pp.

Reviewed by B.J. Hollars

The day after Silvan is born, Monica Wesolowska learns her son is not all right. In fact, he is the opposite. First, there is a blot clot, then a seizure, then a coma, and finally, a diagnosis: hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Yet the doctors’ ability to identify the ailment hardly serves as a cure. Rather, recognition of the infant’s oxygen deprivation functions as the death knell, confirmation of the “not-all-rightness” which will continue for thirty-eight excruciating days before his breathing stops for good. Yet between Silvan’s first and last breaths resides a story; one told with such candor that the reader knows not whether to reward Wesolowska for her brutal truths or plead for a lie, instead. When faced with the reality of their son’s hopeless future, Wesolowska and her husband make the difficult choice to remove Silvan’s feeding tube. “What we are doing for Silvan feels compassionate,” Wesolowska rationalizes, “what we are not doing is euthanasia…” Yet the words themselves fail to bear the burden of their meaning. It is a trope Wesolowska examines throughout: the ineffectiveness of language. When a friend asks Wesolowska if Silvan should die on his own, the mother thinks, “How relieved I am that she is someone who can use that word ‘die.’” (Wesolowska, herself cannot.) Later, when describing her love for her son, Wesolowska notes that, “what other people call ‘love’ is a lie, a mere convenient word.” Wesolowska’s own words, however, are never convenient. In fact, they are the words we least want to hear. Nevertheless, she spoons them down our throats like medicine, demanding we take our dose whether we like it or not. And we won’t like it. Despite the grace and bravery in Wesolowska’s words, we will find it difficult to enjoy the story. How can one ever enjoy a subject so raw it defies the words themselves? Reader beware: Wesolowska will break your heart beautifully, and she has no intention of fixing it.