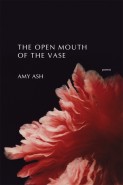

Book Review: The Open Mouth of the Vase by Amy Ash

The Open Mouth of the Vase

Poems by Amy Ash

Cider Press Review, January 2015

ISBN-13: 978-1930781184

$17.95; 58pp.

Reviewed by Nancy Posey

From the first poem “After Dinner” in The Open Mouth of the Vase, Amy Ash recognizes the small details that are open to interpretation, noting how easily one “might mistake / a heart attack for a serenade / if you paid attention / only to the gestures.” Ash not only pays keen attention to such details but also to their ambiguities, the interplay of appearance and reality—a woman cupping her hands to catch cigarette ashes “as if blowing a kiss / across the room.”

More poignant than these observations of strangers, though, are those poems that inference life at home. The speaker’s mother in “Prayer” teaches her how to pray, “bent low, / hands pressed together as if to dive” into the cool satin sheets of the bed. . . “without even looking up at the crucified figure on the wall. “Gutting” describes a fishing trip with her step-father when she was seven in unsettling images—a fish flops “in epileptic seizures,” its “slick white belly slit open / like an unbuttoned blouse. Like a young girl, helpless / and naked . . .”—and notes how he hands her the fishing pole, the gutting knife “as if we had done nothing wrong.” Likewise, “Domestic Scene” is reminiscent of Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz.” Set too in a kitchen containing the tensions of an angry house, her mother does the “woman’s work” as the father—or perhaps the step-father of the earlier poem—“come[s] home from the butcher shop, stench / of blood on him,” leaving her mother to take responsibility for his spill as she raises her “flag of surrender.”

Ash maintains a careful balance between dark and light, offering humor, tenderness, even playfulness. She places “Acme Book of Love,” with its allusions to the maneuvers of Wile E. Coyote in his constant pursuit of the Roadrunner, just before “Question and Answer,” a lesson in life and physics. The persona of a teacher envisions her students as birds “flap[ping] their returned essays / in a flurry of exit,” telling them, “There is no need to take notes / because all of this / will be on the test.”

These poems take readers to out-of-the-way places: to an awkward coupling in “Public Rest Area, I-90,” with cleaning instructions alternately placed between the lines of the narrative’s action. Some poems document road trips. In “He Said Come-On,” a road heads east from New Mexico through “Texas Texas Texas” toward “Alabama or Arkansas / to the beginning of the alphabet.” While riding, the speaker in “Next Exit” engages in a fantasy of an encounter with the driver of an eighteen-wheeler sharing the road.

Ash’s attention to the sensory, particularly to sound and taste, as implied by the title, enlivens her work. Shirts hanging on the line to dry invite embrace; in “Self Portrait in a Hotel Pool,” her “bird[s] / punctuate the sky / with their sad ellipses.” Whether describing the city landscape after a hurricane or the winter “air like cracked glass,” she brings the reader into the scene with fresh imagery, steering clear of cliché.

Over the course of the collection, readers feel privy to the speaker’s most private thoughts and experiences. In “Why We Will Not Have Children,” the speaker gives insight into the couple “still awkward / in [their] marriedness.” Even anticipating fights leading to smashed plates, she confesses, “if he were to ask me again / I would say yes.” These poems, too, invite readers to turn back to the beginning and read again.

Nancy Posey has taught English at high school and college levels for 27 years. In addition to book reviews in various print and online journals, she has published essays and poetry, including her 2009 chapbook Let the Lady Speak. A voracious reader and writer, she maintains a book blog, The Discriminating Reader. She recently moved from North Carolina (“The Writingest State”) to Tennessee, where she continues to teach as an adjunct professor and plays her mandolin.

Leave a Reply