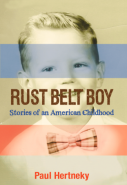

Book Review: Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood by Paul Hertneky

Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood

Paul Hertneky

Bauhan Publishing, May 2016

ISBN-13: 978-0872332225

$21.95; 224 pp.

Reviewed by Renée K. Nicholson

“Like tempered steel, the locals have been made sharper and stronger through extreme stress.” Paul Hertneky, in his memoir, Rust Belt Boy: Stories of an American Childhood begins at the end, locating us in current-day Ambridge, Pennsylvania, a town on the western outskirts of Pittsburgh. He brings us to this place to take us back in time, showing us how this small industrial town grew from a tiny outpost. Living in the rust belt, in “a border town between the Northeast and Midwest,” Hertneky’s parents, children of immigrants, met, married, and built their life in shadows of industry and manufacturing. Ambridge, we find out, was named after the American Bridge Company, and its residents identify as “Bridgers.”

Peppered with reportage-like segments and historical accounts mixed with personal narrative, Hertneky places himself both within Ambridge and outside it, using place as the thread that holds his narrative together. In Hertneky’s writing, not only does a sense of place matter, a sense of this particular place matters to the story that unfolds there. “The sidewalks of Ambridge in the 1960s were jammed with pedestrians running their weekly errands. And, on most evenings, Merchant Street, lined with shops, bars, and restaurants, gleaming with shiny cars and neon signs, drew families that walked arm-in-arm as they might in Naples or Athens.” The Ambridge of Hertneky’s youth teems with civic life, church life, family, and possibility not yet tamped down by the shadow of the large manufacturing plants. Ambridge is also characterized by the many immigrant groups that make up its hardworking population, from all over Eastern Europe as well as Italy and Germany. Neighborhoods come to take on the character of these homelands, becoming little enclaves. The town itself reveres certain things collectively, church, family and football chief among them, bringing cohesion to the many ethnicities.

The book’s structure strikes a balance between essay collection and memoir. Beginning and ending with the frame of current-day Ambridge, and in between moving back in time to the young adult Hertneky working shifts at one of the manufacturing plants, the book then moves even deeper back into history, both of the town and of his family. From this vantage point, Hertneky presents a more linear trajectory of childhood, college, first jobs and loves, towards present day. Each essay functions both as a stand-alone unit and part of a larger narrative that lends itself to a linear reading. At times Rust Belt Boy covers and retraces familiar ground, and although there is repetition, it’s easier to follow his emotional threads by reading it as memoir or narrative arc from start to finish.

Parts of the book that stand out as particularly evocative writing include Hertneky’s writing about the smells and tastes of Ambridge’s traditional foods. In describing the delight of eating pierogi cooked by volunteers at his Catholic elementary school, Hertneky writes, “With my fork I cut the firm potato pillow in half, exposing the fine filling” while also ordering extra kraut from the grandmother’s wielding spoons.

Though many of his Baby Boomer childhood memories read idyllic, there are two things that tug on Hertneky’s narration. The first is the impending and then actual collapse of industry in Ambridge. The second is Hertneky’s own wanderlust. While he feels the ties to home and family acutely, much of what Hertneky writes about circles around the need to leave Ambridge. Even the pull to stay near his high school love is not enough to fasten Hertneky to his hometown, or even the Pittsburgh region. By the end, we witness his escape: “I packed everything I owned into the Civic and hit the road,” Hertneky writes of his younger self.

Even as Hertneky physically leaves Ambridge, he feels its imprint on him—from the shoes he wears that he finds out of step with the fashion in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he first travels, to the accent he takes from the town in which he grew up. The latter never leaves him. Hertneky paints a vivid picture in the early chapters that come to fruition late in the book as the revelation that he will always be “a son’s attachment.” We see his view of Ambridge from a local’s perspective, with the clarity that only distance can clarify.

Renèe K. Nicholson is the author of Roundabout Directions to Lincoln Center, and her work has appeared in Poets & Writers, The Superstition Review, Moon City Review, The Gettysburg Review, and many other publications. She is an assistant professor in the Multidisciplinary Studies Program at West Virginia University, with discipline specialties in creative writing and dance. Renèe was the 2011 Emerging Writer-in-Residence at Penn State Altoona and is Assistant to the Director of the West Virginia Writer’s Workshop.

Leave a Reply