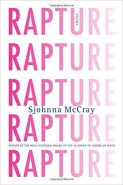

Book Review: Rapture by Sjohnna McCray

Rapture

Poems by Sjohnna McCray

Graywolf Press, April 2016

ISBN-13: 978-1555977375

$16.00, 80 pp.

Reviewed by Ryan Boyd

Contra Tolstoy’s famous opening to Anna Karenina, it is somewhat misleading to speak of happy or unhappy families, because those adjectives describe a dichotomy, while reality seems a lot more like a spectrum running through loss and misery to loving contentment and even joy. Into this blurred reality comes Sjohnna McCray’s debut volume, Rapture, alert to the work of living with the past and present of a family and armed with ecstatic language.

Turbulent families are not a new topic, of course; what matters, as with any material, is the use to which a writer puts it. Rapture is not solely about families, and neither is it pure autobiography, as much as McCray evidently mines his life. But family is the book’s thematic anchor. From this, McCray spins out meditations on war, growing up, travel, the roots and uses of poetry, the adjunct ambiguities of love, of partnership and parenthood. This is a deeply psychological book about the body’s ecstasies and failings, about the tension between the self that wants to be autonomous and the impulse to love another and give up fantasies of independence. Forgiveness is how the poems acknowledge the world: forgiveness, the act of responding honestly to forces that make love difficult, which paradoxically creates the possibility of a loving future.

McCray’s lyric personae have a unified rhetorical voice and describe a coherent arc of events on a relatively progressive timeline. There is a bildungsroman element to Rapture: the speakers, those spiritual accountants, work out a fragmented but ultimately cohesive narrative, which moves from a lonely childhood to awkward young maleness and finally to the tenuous maturity that, if determined and a little lucky, an adult attains. McCray’s formal dexterity enriches all this, because the variety of structures he works in—prose paragraphs, rhymed and unrhymed couplets, William Carlos Williams-style “stepped” stanzas, quatrains, lines far out on the range of the page, hybrid forms—evokes the heterogeneity of experience.

Rapture begins in wartime. The speaker’s father is an American soldier stationed in Asia, his mother a Korean prostitute working beneath “light / reducing men to texture” where “bedsprings in their frailty squeak” (“Comfort Woman”). Rather than play this for ghoulish or gothic interest (the Baudelaire route), McCray locates real sweetness in the flowering of love amid war. Two people whose bodies don’t much matter on the world’s market, save as sexual commodity or cannon fodder, come together and briefly flourish:

…………He hooked his arms through hers as if

they could stroll the lane like an ordinary couple:

…………the unassuming black and the Korean whore

in the middle of the Vietnam War. (“Bedtime Story #1”)

McCray is deft with endings—closing scenes, revelations, last shots, peak knowledge. However, the “as if” and the cold, sociological nouns (“black,” “whore”) draw a shadow over the scene. Worse times are coming. Love is not a shield.

Later a speaker’s family establishes a life stateside, but their ambiguous identity frightens the neighbors. In “The Savages in the Suburbs,” the sight of an interracial family shocks, and it isolates the young speaker: “Blinds are cracked and shades snap up as the neighbors follow us like klieg lights.” Soon the father’s body, already wrecked in war, collapses, followed by the mother’s mind. In “Three Ways to Scat About a Leg and a Father,” the speaker envisions his dad as a vagabond poet—“With sores that shine like sequins, the body, he riffs /-/ is like a neon sign: sometimes on & sometimes off”—while “Agnostic Front” depicts his death with stunning imagery: “I believe the spine was stolen / right out of my father’s back. /-/ Slumped at the kitchen table, / he doesn’t move.” One of the book’s most powerful poems, “Asylum,” depicts the speaker institutionalizing his mother, who has succumbed to dementia and become a ruined Sisyphus: “She looks at the boy and pushes / with all her might the rock up the hill / to recognize him, to stay in the moment, / to silence the wind that carries her name[.]” But that boulder rolls back.

The male narrators of subsequent poems venture into the world on their own. “Balanchine’s Prodigal Son” depicts a jean-jacketed wanderer’s “first night in Manhattan,” where in “the elixir of lights of this corporate- / sponsored space station” he begins to shed “The gravity of the Midwest” and finds “the promise / inherent in this landscape.” For a young man, much of this promise is erotic, and from this point on the book thrums with sexual energy.

“Glorious Hole” is a genuinely moving albeit unsentimental lyric about a form of desire not often welcome in American public life. It is a love poem for the marginal; at the same time, its tragic view of love (always doomed to fail at lasting in the world) fits a tradition that goes back to Wyatt and Sidney:

In a place without light, we have our sex.

The cool harbor of bathroom floors,

the cerebral smell of tile. I wait

with mouth open, adjacent to the rim,

for fluid perfect and unclear. I wait

for a place where cells won’t die

in the mouth but leap off the tongue—

wise and physical like gods.

As Rapture shifts toward its finale, the initial ecstasy of city life moves into more settled adulthood. The final, titular poem is divided into eight smaller pieces. “I’d Rather Be Eating” praises takeout on the couch with one’s partner, while the speaker of “Civil Union” looks at his man and “imagine[s] us as soldiers / locked down in a trench under the tarp / of a foreign night.” Partnership is a “dual surrender,” potentially boring at times but stable and invested with meaningful habits and routines. The book closes in sexual ecstasy framed by the rhythms of a long-term relationship. The speaker and his lover draw back from the moment of orgasm, followed as it often is by a feeling of separation and loss, and hold themselves in joy: “And still, we refuse to yield /-/ back into being singular.”

What McCray accomplishes here is to convert private suffering into nobility, in terms that are recognizable to a reader yet irreducibly strange, like another person’s life always is. “Rapture” the noun derives from the Latin raptus, “seized”; Rapture the book pulls the reader correspondingly close. This is a fine debut indeed.

Ryan Boyd teaches at the University of Southern California and lives in Koreatown, Los Angeles.

Leave a Reply