Book Review: Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System by Sonya Huber

Reviewed by Rhonda Lancaster

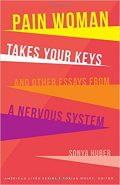

Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System

Essays by Sonya Huber

University of Nebraska Press, March 2017

$17.95; 204 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0803299917

Recommend a book of collected essays about one woman’s pain and you might receive an incredulous look. Spending several hours reading about someone else’s pain might seem like a masochistic endeavor; however, Sonya Huber’s poetic descriptions and self-deprecating humor about her rheumatoid arthritis keep Pain Woman Takes Your Keys and Other Essays from a Nervous System from being a painful experience.

In the Preface, Huber clearly states her intention in collecting these essays, “my goal … was not to fix or provide advice…but to explore the landscape.” She acknowledges that there is a “vastness” to the land of pain and hopes that she is “not confounding or isolating anyone else in pain.” It is a sincere introduction and a goal that she successfully achieves.

Huber divides the book into six categories. She uses the first section, “Pain Bows in Greeting,” to define pain and its effects on her life. “Side Projects and Secrets Identities” helps illustrate how pain bifurcates her life and identity. “My Machines” might be the most current section as it focuses on how technology is both an escape and a barometer of her pain. While Huber includes asides throughout the book on how to not speak to a person with the invisible illness of pain, it isn’t until the fourth section, “Bitchiness as Treatment Protocol,” that she lets loose her full rants about others’ attitudes toward pain. By the time the reader reaches the fifth section, “Intimate Moments with the Three of Us,” we are ready for this personal discussion of pain and its effects on her sex life with her husband. Finally, she brings the collection to a close with “Measuring the Sky,” which encourages the reader to reflect on what she has read about pain and to possibly take action toward supporting research or simple understanding.

Pain Woman is described as an unconventional collection of essays, and Huber makes use of a variety of formats to expand her lexicon of pain. She begins the collection with a list poem titled, “What pains wants,” which provides an excellent (and perhaps unintended) summary of all the topics that will be addressed in the book, from the descriptions about how pain makes thinking impossible to the emotional chaos it can wreak. It also introduces Huber’s uniquely poetic voice, “Pain puts its beaked head in its long-fingered wing hands in frustration and loneliness.” These concrete descriptions of what is otherwise an invisible feeling provide a clear picture for the reader. While many of the essays are more traditional, the sprinkling of the unusual helps lighten the reading, such as “Prayer to Pain” that closes the first section. Despite the title, it isn’t actually a prayer directed to pain; she doesn’t ask pain for anything, rather in five prose-poem paragraphs she describes what pain is and what it wants from the sufferer: “You must look pain in the eyes like a child and tell it not to be afraid of itself.” This reference to talking to pain the way one speaks to a child captures the sense of the insensibility of pain, the inability of the sufferer to reason with it.

Huber imbues each essay with her experience and with an expert observational eye, but she also supports her experience with quotations or statistics from the larger pantheon of pain literature. One of her frequent complaints about the reactions from people who she knows intimately or as acquaintances or even strangers who see her hunched over her cane is a frustration that they always offer advice: “Have you tried…?” they ask. In person, she bites her tongue. She knows they are trying to be helpful, but in print, she shows her exasperation, “I felt my intelligence being questioned, because as a responsible person I would look into every possible solution.” She recognizes that every adult has suffered physical pain at some point in life and that most do not understand the difference between the acute pain of a sore back versus the chronic and debilitating and unpredictable pain of disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia. She does not have the answer for these well-meaning people. She quotes Arthur W. Frank, author of The Wounded Storyteller, “absence of solution makes mysteries a scandal to modernity” before concluding, “I exist in the scandalous state of illness.” We walk away, not with a better way to react to those who are in pain, but with a reminder that we are not being asked to solve pain, but to listen to it.

One of the most enjoyable chapters is “Peering Into the Dark of the Self, with Selfie” as Huber analyzes her own penchant for taking “pain selfies”: “my eyes lidded at half-mast…With neither a smile nor scowl, these faces are as close to the naked self as I might ever capture.” She doesn’t post these selfies online, rather they remain on her phone as a personal record of her own journey as the pain flares and recedes. However, in the chapter “The Status of Pain,” a friend she runs into at a writing conference comments, “All I see on your Facebook page is ‘Pain, pain, pain.’” This sends her into the rabbit hole of reviewing a year’s worth of status updates. She creates a long list of updates, but discovers only six posts about her illness with three being links to content created by others and only two where she uses the word “pain” in relation to her own status. The rest of her posts—about popular culture interests and family trips and books she’s reading—show another picture of a well-rounded and seemingly healthy individual. She wonders if the friend had been exaggerating, a way to rib her, or if, because the mention of pain is “searing” and “creates an emotional connection” that those posts were what he remembered.

The final two sections are both more personal and yet the most universal. When Huber describes how pain management affects her sex life, we can all sympathize. Sexual desire and our needs in bed are difficult to discuss in most relationships, but Huber and her husband have the added layer of I-desire-you-but-my-body-says-no or I-desire-you-but-I-must-decide-if-this-is-a-week-I-can-lose-to-the-pain-that-follows. When she agrees to write an article about her sexual relations with her husband, she half hopes he will forbid revealing these intimate details; instead, he enthusiastically supports it. The last section deals most directly with her experiences with the medical world and most of us can apply our own frustrations with the system to hers. She reviews the various pain scales devised to help communicate her pain to medical professionals, but none accurately describe her pain the way she wishes she could. And so, she ends with a poignant reaction to the doctors who dismiss her current state as “lucky” because she has not yet been deformed by the arthritis: “the body’s outward signals, as mute as a nautilus shell’s smooth surface, cannot speak about the sharp and segmented poetry within.” It is fitting that she should choose such a poetic description to wrap her final thoughts and it is one that stays with the reader.

A former journalist and public relations manager, Rhonda Lancaster holds an MA in creative writing and literature. She currently teaches dual enrollment English and creative writing in Winchester, Va. She’s worked on student publications since her first piece was published in her middle school creative arts publication. A certified Teacher Consultant for the National Writing Project, she teaches young writers’ workshops with Project Write, Inc. She is a member of WV Writers Inc. She lives with her husband, two dogs, and a school of fish in Capon Bridge, W.Va.

A beautiful consideration of a beautiful book. As one who deals with chronic pain, thank you for your empathy, for recognizing the power of this book, and for sharing the work of this extraordinary author.