Book Review: Open 24 Hours by Suzanne Lummis

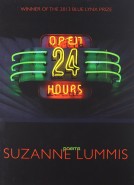

Open 24 Hours

Poems by Suzanne Lummis

Lynx House Press, 2014

ISBN-13: 978-0899241388

$16.95; 103pp.

Reviewed by Lee Rossi

Of all the distinctive voices to have emerged from the L.A. poetry scene over the last thirty years none is, perhaps, as seductive as Suzanne Lummis. Lummis’s poetry is an aquifer fed by many underground streams: her studies with Philip Levine, her passion for film noir, her teaching, journalism and playwriting, not to mention her interest in humor and performance. It’s been 25 years since her seminal anthology, Stand-up Poetry, first appeared.

Lummis’s third collection, a caustic miscellany of L.A. life entitled Open 24 Hours, is an uncommonly skillful blend of wit and wry wisdom. In “Hot Pursuit,” the battered doorway into the book, she tells us, “Here is the art of disaster, the art / of the split-second fatal bad choice,” thereby declaring herself a latter-day (downmarket) Elizabeth Bishop. And in “Red Shoes” (a look she has cultivated in the four decades of our acquaintance), she offers a similar not-quite-full disclosure, “None of them fit. / Only the color fits, color of damage, bad / luck and bad calls.”

Hers is the art of the dramatic monologue, sometimes in her own idiosyncratic voice, sometimes impersonating figures from myth and fiction, Medusa and Eurydice for example. Mostly, she muses on Life, that cruel humorist, but fortunately for her readers, she never takes herself too seriously. “Tenement Lexicon,” for example, a list poem in two sections, is both amusing and revealing. The first part, “What I Am Called,” includes: Miss Lady, the Writer, and Tough Little White Girl. The second, “What I Should Be Called,” includes longer, more literary sobriquets, but their tenor is not so very different: Our Lady of Financial Sorrows, She Who Should Be Paid Attention To, and Frank O’Hara in a Joan Didion Mood. That last epithet is especially revealing, implicating as it does the two poles of her literary imagination, the tough-minded Californian and the more whimsical, l’art pour l’art New Yorker.

This linking of the two literary centers reminds us just how close NYC and LA really are. Both have a taste for the cool and ironic, as well as a penchant for excess. Lummis can rant with the best of them, as for example in “Aspire to Be Less Stupid – or – Shoot Me Before I Post Again,” in which she responds to the bilge clogging the internet:

To Terry who calls Obama a Muslim,

a Marxist, a Communist . . .

this is my last post:

Many thanks for the helping of preposterous

accusations, refried urban legends, program-

matic clichés, and – to top it off – colorful

paranoia sprinkles.

Despite her attention to failure and loss, there is also an unmistakeable esprit to the Lummis persona. She loves poetry, loves its conventions and taboos, loves the permission which art gives her for playful transgression, as for example, in a series of poems inspired by “rules” set by other poetry teachers. These “rules,” which she then violates in her poems, include such injunctions as: “Never write a poem about a woman with a chameleon on her hat,” “No self-pitying poems,” and “Never use the word ‘soul’ in a poem.” My favorite is #8, “Don’t steal other people’s lines,” which becomes the epigram for a poem entitled “Too,” which I reproduce in its entirety:

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the Negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix too!”

Just when we begin to think that her art is simply a matter of dramatically struck poses, however, she’ll toss in something serious, something suggestive of real human suffering, as for example the quote from Sufi scriptures at the end of “Soul Fillet”: “I was a hidden treasure / and I desired to be known.” Or she’ll insert something heartfelt and direct, as in “The Not Sonets”: “There’s a mystery at the heart of this poem that I don’t understand.” She’ll even venture the hortatory, as in “Short Poem Demanding Massive Social Action”:

People, why keep blaming the world . . .

Fling open your windows,

throw out the old way of thinking.

The fact that the narrator of this last poem has a tremendous hangover and is preternaturally irritable only partially vitiates the force of her declaration.

In Lummis’s art even losers are transformed into something shimmering and wonderful. Poetry is where you find it, in this case in the mean streets of LA where “As much poetry leaps / up from hell as wafts down from heaven.” Whatever its source poetry emits a dangerous, almost radioactive energy, as she ruefully admits in “The Night Life is for You,” the book’s valedictory poem:

the way words and meaning

pull away or push against till

something snaps, and that cry

we don’t recognize is ours.

“It’s fate,” she assures us, “your fate, and it’s open / twenty-four hours.”

Lee Rossi’s latest book is Wheelchair Samurai. His poems, reviews, and interviews have appeared widely. He lives in Northern California.