Book Review: Monsters in Appalachia by Sheryl Monks

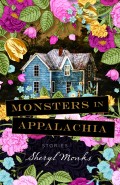

Monsters in Appalachia: Stories

By Sheryl Monks

Vandalia Press, November 2016

ISBN-13: 978-1943665-39-6

$16.99, 192 pp.

Reviewed by Ryan Boyd

In the 1840s, Edgar Allan Poe published an itinerant column (it hopped from one failing magazine to another) called “Marginalia,” where his concerns were, broadly speaking, poetry and politics. In one of the installments, “The Name of the Nation” (1846), he contends that “America” is not a “distinctive” name, because it can refer to places besides the United States, and proposes renaming the country “Appalachia,” a lyrical indigenous word that, he claims, honors the natives whom whites dispossessed yet suits the young nation’s vigor: “nothing could be more sonorous, more liquid, or of fuller volume, while its length is just sufficient for dignity.”

The rechristening didn’t pan out. Appalachia, where I grew up (Alleghany County, Virginia), occupies a strange place in American history, because it has long been locked into a dialectic of neglect and reverence. Treasured for its stunning mountains and valleys and praised for the hardiness of its people, Appalachia is enormous, running from southern New York down through north Mississippi, with its heart in the great hillbilly nexus of North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Without its wood pulp, there would be fewer glossy magazines and literary journals. Without its coal, the electricity that powers Macbooks would be more expensive. Without its music, American pop culture would sound quite different. But in many other respects, Appalachia is a forsaken zone, often mocked as redneck heaven, pure Trump country; stricken with high rates of poverty, addiction, disease, and suicide; and environmentally devastated by the industries that give a decreasing number of its men and women a subsistence wage. I still remember the sodden clear-cuts, and the octopus of a paper mill that stank up the Jackson River Valley. To borrow Faulkner’s ethnographic term, Appalachia is Snopes country.

Monsters in Appalachia, Sheryl Monks’ debut collection, consists largely of Snopes stories. Sometimes these entail confrontations between local elites and poor people, as in “Clinch,” where a mountain family comes to town for supplies and encounters the arrogant sheriff while Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” speech plays in the background. But the ruling class, such as it is in Appalachia, doesn’t show up much in Monks’ stories. Most of the time, economically precarious (though not necessarily impoverished) whites own the stage.

And what stage is that? In one of his many perfect turns of phrase, Gore Vidal calls the novel “our lovely vulgar and most human art.” Of all genres, novels are the most densely populated and expansive realms of action, more heterogeneous in their world-building than, say, lyric poetry, which is concerned with one speaker’s response to experience. Literary fiction, with its heightened attention to style as much as to plot and character, approaches the condition of a multi-voiced poetry, particularly when a narrative adopts free indirect style, blending the characters’ voices with the narrator’s or novelist’s perspective. This magic trick is especially intense in short stories, where there is less plot exposition than in a novel, and where the cuts of characters’ lives are shorter and more psychologically concentrated.

What emerges from Monsters is a minute anthropology of violence, some forms of it intensely present, others what we might call “infrastructural”: the violence of factories and mines (“Out from the little hollows where they clambered bent-backed into the earth to mine the black diamonds that enslave them,” observes a travelling magician); of failed marriages; of bonds between mothers and teen daughters; of Vietnam; of school buses ruled by small tyrants; of poverty; of sex (e.g., “a surge of power inside me like a burning tornado, a volcano turned inside out”). Sometimes violence is rendered humorously, like in “Nympho,” the tale of two middle-schoolers obsessed with the prettiest stoner girl in town, which plays like a Richard Linklater film. But most of the time the violence is grim, with the usual grubby stakes, and a mood of dread shadows everything. Witness the terrifying “Justice Boys,” in which a gang of outlaws pursues the wife of a man they hate down a dark rural highway; or the black comedy of “Crazy Checks,” where an electrocuted factory worker “just stood there conducting electricity like a cheap Taiwan toaster.”

Monks’ attention to immediate consciousness is granular and gripping. In the first story, a badly traumatized woman who killed her abusive husband stares into a void of burning coal slag and pines for her children. She is drawn obsessively to the toxic landscape, a mirror of her own life: “It was the kerosene burns on the babies what found her negligent, sores where they’d crawled through raw fuel that one of the older ones had sloshed when filling the heater. Most people said she’d lost her sense from being beaten so often in the head, but they showed no pity on her. Now here she was, wandering the hillsides like a revenant.” The next narrative takes place in another coal hell—an unstable mine. “Already, they have cut a strip in both directions,” sweats the narrator, “and soon they’ll be coming back through the middle, robbing pillars it’s called,” his mind churning up the ironically poetic idiom.

There are actual monsters in these pages, too. Monks saves them for last, the magic-realist title story. Melding the horrible and the comic, it depicts a countryside overrun by strange creatures, and involves, for instance, a hideous, bat-like fallen angel sharing a dinner with the elderly couple who own and employ him as a tout for their roadside freakshow, which is composed of other captive demons, some of whom they eat. Mountain tradition gets conscripted into the service of beast hunting: “Anse’s Plotts are of an olden breed, the keenest ever was. They can scent things never heard tell of. Trees? Why that must be simple, she guesses. She herself can scent trees, pine rosin and fruiting pawdads, thought not at a full tear through the dark.” The old mountain woman and her man, stock Appalachian characters, enter apocalyptic modernity, and the story closes with a Biblical vision of the world’s end.

Appalachia is a place of frustrated longing. This informs the traditions of its fundamentalist Christianity, which craves a purified world. It fuels the outlaw moonshine culture that has given way to a plague of pills and heroin—a stillborn yearning for chemical escape. It shows up in cross-connected economic, geographical, and affective terms: the drive to get out, to find jobs that don’t involve coal or logging or Medicaid. I heeded that longing, heading to college after high school. Now I live in Los Angeles, where most of my neighbors know as much about Appalachia as I do about Oaxaca. Then again, after sixteen years I don’t know all that much about Appalachia either.

Monsters in Appalachia made me want to go back, at least for a visit. To write about Appalachia is to write about America, as Poe realized, even if that is also where monsters are, and Sheryl Monks reports from this countryside as only a novelist can.

Ryan Boyd teaches at the University of Southern California and lives in Koreatown, Los Angeles.

Leave a Reply