Book Review: The Cowherd’s Son

Reviewed by Tom Griffen

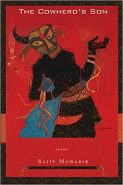

The Cowherd’s Son

Poems by Rajiv Mohabir

Tupelo Press, May 2017

$16.95; 99 pp.

ISBN: 978-1-936797-96-7

Rajiv Mohabir’s second full-length collection, The Cowherd’s Son, depicts the narrator’s journey as a queer, Indo-Caribbean man chronicling an oppressive ancestral past. The speaker bravely unravels a lineage wrought with material loss and compromised traditions. Poems incorporate the derided languages of forbearers: Creole and Guyanese Hindi. Though Mohabir often places English translations nearby, this helpful gesture suggests he is fulfilling an assumed role as the go-between, someone who can bridge the gap between multiple worlds of understanding.

The book’s intention is marked in “My Name is a Map” (part III):

How is Ganga-jal pure when its human filth blinds

every creature that moves beneath its silt?

From the murky slime at the bottom of the lake

the lotus grows, petals unstained by dirt.

Mohabir’s poems are complex, but his use of the page delivers an aesthetically-pleasing geometry. Gentle and consistent patterning creates a familiar tempo even when, as in “Chaar,” lines are laden with less-familiar vernacular or imagery:

Maha rajah jai ho! Cow Minah tek out a-bone wha de inside ‘e

pagri and put ‘em in ‘e had an rub ‘em an a-bone stat fa sing.

Papa, o papa na mash me bone!

Bahadur hamke mareke phulwa luta hai.

Papa, o papa na mash me bone!

Bahadur kill me yondah side an teef me flowah

rose.

The final lines of the title poem offer witness into a queer, mythological, and mixed-caste identification:

Oh Kanhaiya, O Madhav,

My father Ahiri, my mother Brahmin

Now Christian carnivores.

Mixed-caste and queer-countried,

I’m untouchable, the only Mohabir left

who still scores your shloklas.

Content ranges from nineteenth-century indentured servitude where, as in “Blind Man’s Whist,” “Any cutlass deal / will cost an eye,” to “Mysterious Alembics” where the narrator calls his grandmother to “record her voice telling me how to make daal.” The globe-spanning geographic landscape, from Varanasi to London to Niagara Falls, physically represents the challenge of change resulting from transition.

“Touch Me Not” introduces the father. A voice bellows, “Son, you are fit / only for the greasy smoke / of the body burning on its pyre.” This voice continues, “But you are an imposter, suckled / at a dead heifer’s teat, a Hepatitis crow.” The father believes he has been slighted by having a queer son. Feeling refused of the child’s youth, he sends him off with a curse:

When men ask

to which mount you belong,

you will look at their palms,

your own hands stiff

with cow shit stoking a pyre flame.

“The River Son’s Betrayal” is the aftermath wherein the speaker lives a camouflaged life:

I too pretended

much for my mother’s sake,

buried secrets in silt;

swallowed tumult of the adolescent

thrill of wrestling other boys

The speaker’s masquerade is no antidote even if “queerness // was a tool for survival” (“Bound Coolie”). “Gift From Grandmother” marks the falling from familial ranks.

though your five sons

clutch their father’s dhoti.

I’ve always wished

for a crossroads, an option

to buy my freedom,

to save my own hide

In the same poem, the narrator proclaims, “There is no shame / in surviving anyhow you can.” He has inherited such strength from his progenitors.

Mohabir unifies the tumult of migratory life into one place: the human body. The body is exploited, wounded, diseased, and set aflame. Its charred ashes are doused and reabsorbed by the earth. In “Chamber Music,” violent images are softened with bursts of short, rhythmic lines: “Press me. Strings cut / your index, middle, ring.” “Hold me. Smash the gourd.” “Watch me stoke a concerto in your bones.” “Diabetes Prayer” pays homage to ancestral laborers of sugar plantations—their weathered bodies proof of corporeal colonization.

Gods of cane, I too am bent before the grinder,

My tongue swollen and pasty.

Gods of cutlass and gashes unhealed,

a hymn exhales rest in the air; my stitches rip with each inhale.

I drape myself in a shroud,

my ox ribs riddled with fructose scars.

The work of sixteenth-century musician, Tansen, taps into ancient mythology. “Deepak Raga” is based on a Tansen melody believed to spontaneously create fire. Another, “Malhar Raga,” conjures rain. In namesake poems, Mohabir engages this fire and water metaphor to highlight a conflicted identify. In “Deepak Raga” he writes, “Look at the darkness in your temple. / What words will spark your fuse.” The poem continues, “Sienna finches flit from lips to wick. / I catch one glowing ember and / swallow it whole.” A forced ingestion burns the body from the inside out.

The Cowherd’s Son is an impressive collection marked by honest vulnerability. It humbly displays a harrowed family history and the ensuing feeling of being an outlier. Struggles with homophobia, racism, violence, and xenophobia all serve to help the speaker achieve a deeper sense of self-acceptance. Ultimately, The Cowherd’s Son enlists darkness to empower the potential for goodness.

In the conclusion of the final poem, “Unwitting Pilgrim,” the speaker advises against identity categorization: “In fact, stop racing toward / contained closure in this open space.” Repetition in the next line is like a mantra. A prayer. It continues, “In fact, stop reading; stop— // close your book right now.” As if to say, start living now.

Tom Griffen is a North Carolina writer with California roots. In 2015 he received his MFA in Poetry from Pacific University. His work has appeared in Tupelo Quarterly, Prairie Schooner, Crab Orchard Review, Harpur Palate, O-Dark-Thirty, and others. Tom is also an endurance athlete, spoon-carver, and professional speaker in the world of specialty retail. In January 2018 he is beginning a walk across America. See more at www.mywalkinglife.com.

Leave a Reply