Book Review: Cattle of the Lord by Rosa Alice Branco, translation by Alexis Levitin

Reviewed by Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers

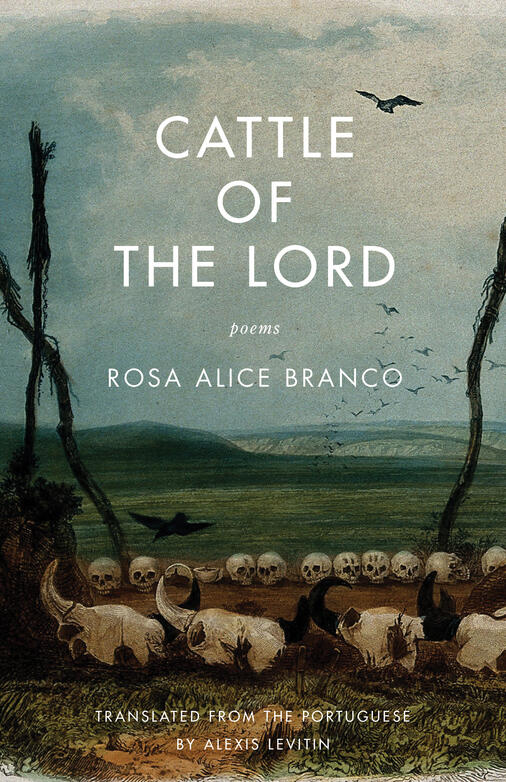

Cattle of the Lord

Poems by Rosa Alice Branco, translation by Alexis Levitin

Milkweed Editions, December 2016

ISBN-13: 978-1-57131-482-6

$16.00; 96 pp.

Rosa Alice Branco’s Cattle of the Lord, translated from the Portuguese by Alexis Levitin, is a cri-de-coeur of creation. In a side-by-side presentation of the original Portuguese faced with the English translation, various first-person speakers cut to the bone with desperate, often anguished, demands to a distant Lord. Yet these poems manage to bridge the mundane and the theological, often in the same breath. As beautiful as they are cruel, these are poems of deep eschatological crisis; after all, “what will you tell the Lord / he doesn’t know or hasn’t been?”

Faith is a central tenant as speakers take turns addressing this Lord—in rage and anguish, hope and despair, reaction and futility. One of the volume’s great delights is the mystery of these speakers. The book begins with “Tasks of the World,” where cattle in the pasture are “devout…snuffling the ground with their white spots / while the black ones raise toward the sky / a bovine gaze.” These cows seem to be a direct reference to the book’s title. However, as the volume progresses, there’s a dawning awareness that just who or what constitutes the Lord’s cattle is much more complex. “Like A Log” seems to speak from a bovine perspective. Yet, an “Exchange of Blood” names humans as the Lord’s cattle, the sacrificial altars “always burning…the blade aimed at human hearts. / Son exchanged for lamb, blood for other blood, / the way one changes shirts.” The personas shift, but use of the first-person pronoun remains unchanged. Without indicating who is behind that omnipresent speaker, “cattle” quickly takes on the overtones of its oldest meaning: chattel, capital, or goods. From this ominous position, Branco’s creation cries out in their faith, or the void where it once existed, “fervent and immense: / the exact measure of our misery.”

But even within the speakers’ unified voice, an ordering emerges. From the outset, the use of the term “Lord” throughout the collection suggests a fealty born of hierarchy, and a separation of the mortal and the divine is a given. Still, within the chorus of speakers, mortality’s the crux. In “Only the Cats,” the cats feel “an unnamed / knot in the throat like all of us. / From the rooftops they say no to the heavens. / They want to make it clear close-up.” They share human’s knowledge of death, perhaps even eternity. But, “Animals do not aspire to eternity. / That must have been the substance of the soul denied them.” To the degree that speakers address questions of the soul, mortality demonstrates distinctions. Humans too have “a trembling, almost a consciousness / of having a body,” but it’s the soul, “a human luxury,” that both elevates and isolates them from the rest of creation.

While souls make humans akin to the Lord, it’s usually in the most terrible ways. In “Noah’s Ark,” the speaker illustrates this fraught likeness while railing at the Lord:

But you alone have killed through heavenly benevolence

and planted such conviction into men

that faith can still move mountains

where landmines crucify like nails.

Oh exemplary Father: your teaching

begins at home and the death throes

of your blessed son never reach their end.

Thus, the Lord, and human mortality in particular, are revealed. Human beings remain poised between two masters—the body and the soul, the earthly and the divine, the mortal and the immortal—call it what you will; and that which supposedly elevates them is not benign. The drama of this opposition emerges again and again, with humans portrayed as the most damned among the damned. As one speaker says to the Lord, “That’s how you made us. You gave us deepest ignorance / and most certain knowledge.”

Throughout Cattle of the Lord, speakers wield their futile agency to beseech an impassive Lord in the face of their mortality. The result is a raw, daring interrogation that demands both contemplation and confrontation. Limbed with lush language, provocative imagery, and sharp sentiment, Branco’s world is beautiful. But, make no mistake, it is foremost a bier.

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers earned a B.A. in English from Penn State and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing and M.A. in Applied Linguistics from Old Dominion University. Her poetry is published or forthcoming in Gemini, The Missing Slate, The New Poet, Gulf Stream, IthacaLit, and Menacing Hedge, among others. Her work has been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize in Flash Fiction and was a semifinalist in the 2015 Crab Orchard Series in Poetry First Book Award and the 2016 Philip Levine Prize for Poetry. A native of Pennsylvania, she currently resides in Buckingham, Virginia.

Leave a Reply