Book Review: Blood, Bone, and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews by Ted Geltner

Reviewed by Ryan Boyd

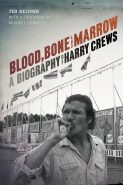

Blood, Bone, and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews

Nonfiction by Ted Geltner

University of Georgia Press, May 2016

$32.95; 448 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0820349237

Literary history teems with versions of the poète maudit, that wandering, tortured, addicted, usually male figure who rejects the norms of bourgeois society and lives instead for a cycle of creation and dissipation. Baudelaire, Berryman, Rimbaud, Hart Crane, Robert Lowell, Bukowski—the roster is longer than a football team’s. But the poète maudit isn’t always a poet. Sometimes he writes fiction, like Harry Crews, who declared in his novel The Hawk is Dying (1973) that “Whatever’s normal is a loss. Normal is for shit.”

Ted Geltner’s lively, perceptive new biography, aptly titled Blood, Bone, and Marrow (the source of all writing, Crews liked to opine), is the first full life of the grimy New South master. Without sentiment and without glossing over the damage it did to Crews’s loved ones, Geltner documents his powerful thirst for alcohol, drugs, sex, and fistfights. Tormented by an impoverished childhood, the loss of his father, and early struggles to break into publishing as a nobody from dirt-poor south Georgia, Crews savored physical risk, especially if it brought pleasure before pain. He was a fixture in the bars of Gainesville, where he taught for years at the University of Florida, as well as on the literary reading circuit, a decidedly boozy network. This led to frequent stints in rehab and brought terrible pain to the lives of friends and lovers (one feels especially bad for his two-time ex-wife and lifelong friend Sally Ellis), a depressingly familiar narrative for an American writer.

But through all of this, Crews wrote copiously and brilliantly. His motto was “Get Your Ass on the Chair,” and he stuck to it through hangovers, breakups, falling-outs, physical ailments, and recurrent depression. Starting with The Gospel Singer (1968), a bizarre tale of deviance and disfigurement set in a town called Enigma, Georgia, which Crews wrote with the help of speed and whiskey (common accompaniments for him), he published over a dozen novels to widespread critical acclaim. His star stayed higher than most writers’ for a long time—in 1988 Madonna and Sean Penn brought him to see the Tyson-Spinks fight, where Donald Trump ushered them to ringside seats—but fame made Crews anxious. He would struggle with it throughout his career, caught between relishing cultural repute and feeling like a redneck outsider.

Blood, Bone, and Marrow illuminates Crews’s life while demonstrating how it fed into his fiction, much of which is at least semi-autobiographical. In fact, his masterwork is arguably a piece of nonfiction, the Bacon County, Georgia memoir Childhood: The Biography of a Place. Geltner’s method is ideal for the first book-length life of an author: it gets all the facts straight, clearing space for more critically nuanced, textually focused studies. It is no flaw that Blood, Bone, and Marrow contains few extended readings of Crews’s published work, because that isn’t what Geltner wants to accomplish. It does leave a reader hungry, though.

One hopes that future books on Crews, whether they are biographies or not, will do three things that build upon Blood, Bone, and Marrow. First, they will exploit the massive Crews archive acquired by the University of Georgia in 2006. Geltner cites those materials—drafts, manuscripts, letters, financial statements, sketches, news clippings, and other miscellaneous papers—but one looks to future scholars to really plumb and organize the depths. Second, they will situate Crews in relation to other American writers, whether these be forebears (like Flannery O’Connor), contemporaries (especially Hunter S. Thompson), or descendants (such as Sheryl Monks, author of the marvelous story collection Monsters in Appalachia). This would entail going beyond individual artists to consider broader trends in the literary world. You could, for example, write a book about how Crews’s journalism for Playboy and Esquire in the heyday of magazine publishing intersects with the New Journalism of Thompson, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Terry Southern. Finally, scholars and critics after Geltner will need to historicize Crews, placing him within the cultural superstructures and socioeconomic arrangements that shaped his writing, and about which Geltner has little to say. Crews is often called a New South writer. But what is the New South? These sorts of questions linger.

But Blood, Bone, and Marrow is still an engaging biography. Geltner’s prose is crisp and vigorous, while his ability to evoke the messy sprawl of Crews’s life while maintaining narrative cohesion is commendable. I hope he writes more biographies like this one; American culture needs a firewall of heroes like Crews, who died in 2012, and biographies help us remember them. Blood, Bone, and Marrow testifies to Crews’s unmistakable grasp of American violence and redemption in an increasingly secular world and leaves one in that paradoxical state good biography induces: mourning for a dead genius, but grateful that his books didn’t follow him to the grave.

Ryan Boyd (@ryanaboyd) is a poet and critic living in Los Angeles, where he teaches at the University of Southern California.

Leave a Reply