Book Review: Across the China Sea by Gaute Heivoll

Reviewed by Daniel Pecchenino

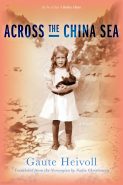

Across the China Sea

A novel by Gaute Heivoll

Graywolf Press, September 2017

$16.00; 232 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1555977849

Near the end of Norwegian writer Gaute Heivoll’s new novel, Across the China Sea, the unnamed narrator asks the fire department to burn his childhood home to the ground. After the deaths of his elderly parents, he found out that the house was falling apart. Or perhaps more accurately, he learned that it was barely holding itself together. For most of its existence, the home was given shape by the people that sheltered within it: the narrator, his parents, his two sisters, and eight “mentally disabled” patients, five of them siblings taken in as children. After everyone that lived there has died or scattered to other parts of Norway, the home built to provide care in a “Christlike spirit of love” loses its purpose and thus its vitality. Burning the house quite literally sends it to heaven: “Later I was told that the fire’s aureole could be seen in most of the parish. First an aureole, then at last the house tore loose from the masonry and rose above the woods. The house rose higher and higher . . . Then it was gone.”

This ritualistic fire connects Across the China Sea to Heivoll’s previous novel, Before I Burn. But where that book’s plot hinged on finding out who was burning down and houses and why, Across the China Sea doesn’t rely much on plot or mystery to keep the reader engaged, but rather deepening relationships. Like works by William Faulkner and (most strikingly) Eudora Welty, Heivoll’s novel is elliptical and reveals itself through the repetition and accretion of details. In this home that blends the domestic and the institutional, intimacy comes from knowing what oneself and others are supposed to do at any given moment. For instance, one of the patients in the house sits under an ash tree every day when the weather allows, taking great care to place the legs of his stool in exactly the same spots as the day before. Another, the narrator’s great uncle, who occupies a kind of liminal space between patient and family member, reads through all of the books in their small town’s tiny library alphabetically. When he reaches the end, he starts over. While these routines might seem compulsive or even depressing on the surface, the house provides a safe space for both patients and family to simply be who they are without inviting analysis or criticism.

The question of where the narrator’s family ends and the patients begin is part of the novel’s subtle analysis of how we treat those with mental disabilities. Three times in Across the China Sea someone compares the five siblings who grow up alongside the narrator—but very much in their own world bounded by the four walls of their room—to animals. While this characterization angers the family, especially the narrator’s parents, none of them seem to think twice about sterilizing the five siblings when they reach puberty. It’s simply something that must be done, the way one must neuter or spay a pet. And while the narrator thinks of the five siblings (particularly one of the girls) as “almost” related to him, “almost” carries all the weight of having or not having freedom. For the many ways that the living and caring arrangements here feel radically anti-bourgeois and truly Christian, they are still governed by institutional bureaucratic norms.

Even with these potential ethical issues, it will be hard for Americans to read Across the China Sea without reflecting on how we tend to deal with the mentally ill. In Los Angeles, they make up a sizable chunk of our homeless population, and according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, nearly two million mentally ill people are booked into U.S. jails each year. Of course, America in 2017 is not Norway in 1945, and one should avoid indulging in nostalgia (especially when getting it from fiction). But Across the China Sea challenges us to do better by focusing our attention on the blurry line between sick and well. Indeed, it seems no coincidence that several of the patients in the house have trauma-induced disabilities against a backdrop of a world still reeling from the trauma of World War II. The novel seems to imply that any of us could find ourselves butting up against the border of what is deemed healthy or normal, which makes treating those outside that boundary with respect all the more imperative. They deserve to be seen, a point the book makes several times. But more than this, they deserve to be lived with.

But Across the China Sea is not a sociological study or political polemic. It is a gorgeously written (and translated by Nadia Christensen) family drama, rich in detail and masterfully structured. Like many of the best family dramas, there’s a loss at the center of the book that fundamentally shapes the narrator’s life. This void remains throughout the novel, and even the burning of the house isn’t a moment of obvious or cheap catharsis. Rather, we leave Across the China Sea understanding that while we can’t change the past or how it’s wounded us, we can always choose to be decent and accepting of difference.

Daniel Pecchenino lives in Hollywood and is an Assistant Professor in the Writing Program at the University of Southern California. He is the Assistant Reviews Editor at the Los Angeles Review, and his poetry and criticism have appeared in Gravel, Two Hawks Quarterly, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and other publications.

Leave a Reply