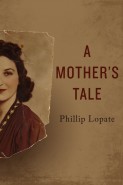

Book Review: A Mother’s Tale by Phillip Lopate

A Mother’s Tale

Nonfiction by Phillip Lopate

The Ohio State University Press, January 2017

$24.95; 196 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-0814213315

Reviewed by B.J. Hollars

In a 2016 interview with Psychology Today, acclaimed nonfiction writer Phillip Lopate remarked, “If someone in my family is getting emotionally bent out of shape, I’ve had to learn to adapt.” In his latest work—a 33-year-old interview with his mother about her life offered in book form—Lopate does just that: adapting his own writing style by allowing his mother’s voice to take the lead. Lopate, meanwhile, serves as an editor of sorts, chiming in to provide counterbalance to his mother’s many screeds. Throughout, he holds her accountable to the less-than-accurate narratives she’s woven into her story. In one instance, as Fran Lopate attempts to pin her squandered dreams of a life on the stage on every available scapegoat, Lopate cuts in to remind readers that despite her finger-pointing, she fails to point the finger at herself. “One recurrent theme in her telling was that she had been frustrated at every turn. Thwarted, thwarted, thwarted,” he writes. But ultimately, “it was she who dropped out of high school, she who chose to obey her sister, she who opted to marry my father, and not to pursue her dream, etc., etc.”

The book’s primary tension comes by way of the mother and son’s perpetual parrying toward the truth: two witnesses to a shared life, though with varied accounts. While Albert Lopate—Fran’s husband, and Phillip’s father—serves as Fran’s punching bag, Lopate, at least obliquely, comes to his father’s defense. It was Fran, after all, who engaged in multiple affairs; Fran, too, who proved incapable of mustering the slightest empathy toward her husband. After Al’s unsuccessful suicide attempt, Fran remarks that she never knew “what he was going to pull next.” Even Lopate appears jarred by her cruelty, commentating: “She sounds so cold here, so unfeeling. Still, I’ve entertained the possibility that sometimes my mother was purposefully putting herself in the worst possible light, exaggerating for the tape recorder, in order to make herself into a more theatrically colorful character.” It’s a theory that complicates both Fran and the book at-large, prompting the reader to wonder if the entire interview isn’t just an act by the thwarted actress.

Readers are continually left guessing, “Who is the real Fran Lopate?” And to some extent, the author, her son, is left guessing, too. Following a particularly sharp condemnation of her husband’s sexual inadequacies, Lopate turns to the reader: “I wonder at her insensitivity in refusing to consider what I, my father’s son, might be feeling, when she would talk about his inability to satisfy her sexually. Was she consciously performing this ritual humiliation of my father for my benefit, as a provocation, or was this simply the mouthing of her interior monologue, no matter who was present?” Admittedly, it’s hard to know for sure. Perhaps the uncertainty speaks to a larger point: namely, that Freud was certainly on to something when theorizing on the complicated relationship shared between mothers and sons. Lopate himself concedes this point, acknowledging the unseemliness linked to their shockingly candid conversations surrounding the subject of sex. “I’ll only say in my defense,” he writes, “that all my life my mother had a way of sexualizing every conversation.” Yet to his credit, Lopate stoically navigates readers through it all, hardly flinching at his mother’s many reveals. By book’s end, the reader is left believing that Fran Lopate was precisely who her son always knew her to be. For better or worse, she was herself.

In lesser hands, such a project would read as naval-gazing of the highest order, an inexcusable indulgence with no bearing on the wider world. Yet Lopate—a seasoned veteran, and hyperaware of this particular pitfall—steers clear of it. “The trick,” Lopate writes in his anthology, The Art of the Personal Essay, “is to realize that one is not important, except insofar as one’s example can serve to elucidate a more widespread human trait and make readers feel a little less lonely and freakish.” It’s a trick he pulls off admirably. Perhaps every detail doesn’t matter, but the accumulation of details does. By offering readers a candid portrait of his mother, Lopate manages precisely what he must: he takes a personal story and turns it outward, and in doing so, he makes it our story, too.

B.J. Hollars is the author of several books, most recently From the Mouths of Dogs: What Our Pets Teach Us About Life, Death, and Being Human, as well as a collection of essays, This Is Only A Test. In February, Flock Together: A Love Affair With Extinct Birds will be published by the University of Nebraska Press.

Leave a Reply