4 Poems Translated by Suphil Lee Park

Four Poems by Korean Women Poets from the 16th-19th Centuries Translated by Suphil Lee Park

Chang-Ahm Jeong

By Choo-Hyang

We row to the blue estuary

Stun birds awake into flight

Mountain marked red by autumn

On white sand no trace of the moon

**

Rowers on water

Stun birds into flight

Mountain autumn-red

Sand bleached of the moon

**

MoveRowBlueRiverMouth

StartleHumanSleepBirdFly

MountainRedAutumnExistentVestige

SandWhiteMoonNonexistentTrace

蒼岩亭

秋香 (?-?)

移棹蒼江口 驚人宿鳥飜

山紅秋有迹 沙白月無痕

창암정

추향

푸른 강 입구로 노를 저어 가니

자던 새가 소스라쳐 날아가고

산에는 가을이 남긴 자국 붉은데

흰 모래에는 달의 흔적조차 없네

Chang-Ahm Jeong has been typically interpreted as the name of a famous Korean summerhouse.

Traditional Korean names consist of Chinese characters, and a courtesan’s name, often two to three letters without the family name, and the name of this poet—supposedly a courtesan—means “Scent of Autumn.”

Song of a Poor Woman

By Heo Nanseolheon

Who’d say I’m not a beauty enough

And I’m good with a needle and loom

But for I come from a poor family

No good matchmaker will see me

Weaving without pause into the night

The loom sobs with cold clicks

This swathe of silk on the loom

Shall make some lucky lady’s clothes

But with the scissors in hand

My ten fingers grow stiff this cold night

Making a bridal dress for someone

Every year I’m to sleep alone

貧女吟

許蘭雪軒 (1563-1589)

豈是乏容色 工鍼復工織

少少長寒門 良媒不相識

夜久織未休 戞戞鳴寒機

機中一匹練 綜作何誰衣

手把金剪刀 夜寒十指直

爲人作嫁衣 年年還獨宿

빈녀음

허난설헌

외모나 자태도 빠지지 않고

바느질도 길쌈도 뒤지지 않는데

어려서부터 집안이 빈한한 탓에

좋은 중매쟁이가 나서질 않네

밤이 깊도록 베를 짜는 손 멈출 줄 모르고

짤깍짤깍 베틀은 차갑게 울리네

베틀 가운데 이 한 필의 비단

필경 누군가의 옷이 될 테지

가위를 잡은 내 손은

추운 밤 열 손가락이 곱네

남을 위해 가례복을 지어주건만

해가 가도 이 몸은 홀로 잠드는구나

Before an independent alphabet system was invented, Korean intellectuals depended on Chinese characters, leading to a high percentage of illiteracy among the lower classes, particularly women. Heo Nanseolheon, a noble, literate (and literary) woman herself, in this poem is writing on behalf of a poor woman who didn’t have the ability to give a voice to her story.

Begging the Magistrate for Rice

By Kim Hoyeonjae

Carefree spirit looms over the Carefree House

I enjoy being carefree by the scenic doors

Much to enjoy but carefree comes from grains

Carefree it is to beg the magistrate for rice

**

Free spirit over Free House

Free to enjoy scenic views

I do, but free comes from grains

Free it is to beg for rice

**

VastSureHouseAboveVastSureSpirit

CloudWaterFenceDoorEnjoyVastSure

VastSureAlthoughEnjoyBirthFromGrain

BegRiceThreeMountainMagistrateVastSure

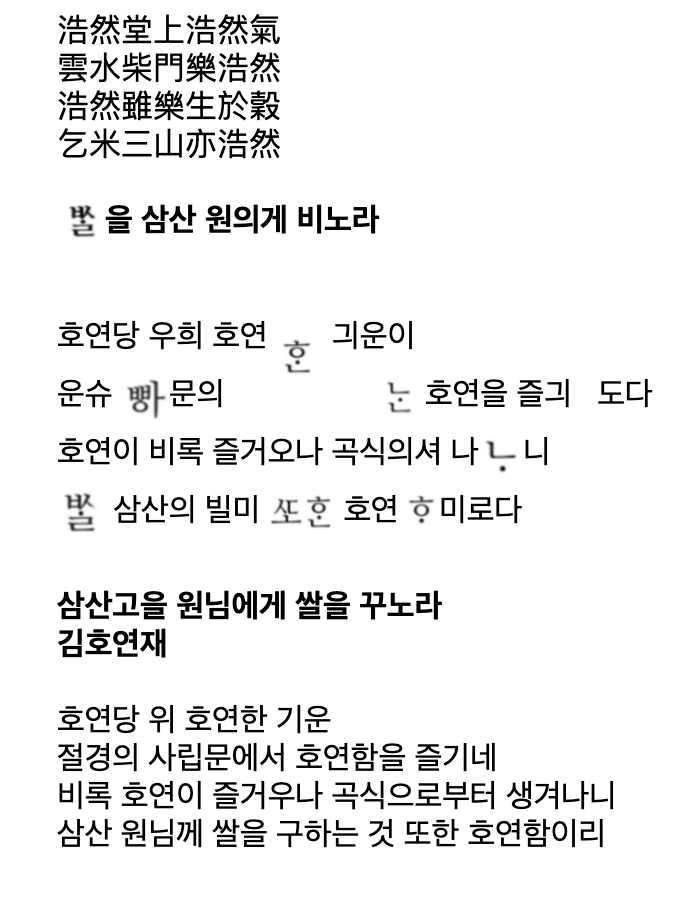

乞米三山守

金浩然齋 (1681-1722)

The poet’s name, Hoyeon(浩然), means water’s flow or a carefree, magnanimous nature, while each character means, roughly translated, “vast” and “sure.” She’s writing a punny poem off her own name here (all “carefree”s are interchangeable with hoyeon).

There’s a Korean tradition to name each house on an estate in order to reflect the nature of its main resident or history. This particular house, where the poet resides, has been named after her, and she’s making it a pun in the poem.

“Cloud” and “water,” put together, refers to scenic views that bring to mind a sort of a paradise in Korean mythology.

三山 here is a one word, the name of the village

The old Korean text is from 여성 한시 선집 (Anthology of Korean Women’s Poetry) by 강혜선 (Kang Hye-Sun) published by 문학동네 (Munhak Dongne) in 2012.

Observation At Sea

By Kim Keum-Won

To the east all water flows

Deep and wide, no end in sight

I see the sky and land, however vast

Are but an armful for my mind

**

All water flows east

Deep, wide, and endless

Vast the world might be

My mind’s vaster still

**

HundredRiverEastDivergeComplete

DeepWideFarawayNonexistentEnd

NowKnowSkyLandVast

PutGetOneBosomAmidst

觀海

金錦園 (1817-?)

百川東匯盡 深廣渺無窮

方知天地大 容得一胸中

바다를 보다

김금원

모든 물 동쪽으로 모여드니

깊고 넓어 아득히 끝이 없구나

하늘과 땅이 크다는 것 이제 알았으나

이 내 한 가슴에 다 담기리

This is a poem written by a female poet who dressed up as a man and traveled Keum-Gang Mountains and the East Sea in a time when women were not allowed to go outside without a chaperone, or to travel with or without one.

Translator’s Note

From a courtesan to a noblewoman who penned an illiterate neighbor’s narrative to a woman who dressed up as a man to travel, these women poets all represent a time in Korea when women were not allowed a voice let alone celebrated, but these poets nonetheless championed the art they loved, often the only form of self-expression available. Their work, composed entirely or mostly of Chinese characters, is also reflective of the country’s unique linguistic history. In lieu of their own alphabet, Koreans depended on complicated, not perfectly compatible Chinese characters for writing (which had a lot to do with the country having been China’s tributary for a long time), leading to a high percentage of illiteracy among the lower and middle classes, particularly women. Then came the invention of Hangul, the Korean alphabet, in the year of 1443, only to be officially acknowledged as the alphabet of the country in 1894 following much political and cultural resistance in the past centuries. Even today, conventional Korean names consist of Chinese characters.

Writing, and poetry in particular, was an aristocratic recreation in ancient Korea. The mastery of Chinese characters required years of education and a linguistic cognition entirely different from that for the vernacular Korean of the time, and writing poems, therefore, a very specific, erudite training—all of which only few could afford. So the women who could write poems at that time, interestingly enough, were either aristocrats or top-notch courtesans who belonged to the class of cheonmin (천민 / 賤民), the lowest of the caste system, virtually slaves who were traded like commodities and whose major duties included entertaining noblemen with their performative, visual, and linguistic arts. So the following poems are not only valuable works of literary art, but also rare historical archives of Korean women from all walks of life (and literally from the highest and lowest social stations), whether the poet meditates, helps other women to be heard, finds something to laugh about in her own misery, or experiences a rare moment of freedom.

In order to reflect Korea’s interesting semi-bilingual history, I first translated the original poems (written originally in Chinese or / and ancient Korean) into modern Korean and then into English. For some of the poems, when possible, I provided a sequential progress in translation, from the most freely adapted to the sound-oriented version faithful to the original syllable count, and finally to the most literal, meaning-driven, and condensed, to testify to the contextual interpretability of the original.

For the translations and revisions of the following poems, I referred to and found many helpful insights and textual guidance in 여성 한시 선집 (Anthology of Korean Women’s Poetry) by 강혜선 (Kang Hye-Sun) published by 문학동네 (Munhak Dongne) in 2012, and 허난설헌의 시문학 (Heo Nanseolheon‘s Poetic Literature) by 김명희 (Kim Myeong-Hee), published by 국학자료원 (Center for Korean Studies) in 2013.

Suphil Lee Park (수필 리 박 / 秀筆 李 朴) is the author of the poetry collection, Present Tense Complex, winner of the Marystina Santiestevan Prize (Conduit Books & Ephemera 2021) and has recently won the 2021 Indiana Review Fiction Prize. Born and raised in South Korea before finding home in the States, she holds a BA in English from NYU and an MFA in Poetry from the University of Texas at Austin. She’s a literary agent at Barbara J. Zitwer Agency that specializes in translated Korean literature of world-renown authors such as Han Kang and Kyung-Sook Shin. You can find more about her at: https://suphil-lee-park.com/

Choo-Hyang (추향 / 秋香) was a courtesan based in Miryang, believed to have lived in the mid-Joseon dynasty.

Heo Nanseolheon (허난설헌 / 許蘭雪軒) (1563 – 19 March 1589), was a Korean painter and poet of the mid-Joseon dynasty. She was elder to Heo Gyun, a prominent Korean writer of the time credited as the author of The Tale of Hong Gildong. She led an unhappy married life, shunned by her husband who was intimidated by her talent. While recognized by Chinese and Japanese literary critics, her work was criticized and neglected in the Korean literary scene at the time because of its subversive nature. She died at the age of 26.

Kim Hoyeonjae (김호연재 / 金浩然齋) (1681-1722) is a Korean poet of the mid-Joseon dynasty. She is one of the few prolific, well-documented female Korean poets from the dynasty, who wrote over 200 poems, which her daughters in law copied and preserved to hand down generations. Despite her aristocratic background, Kim had to cope with an impoverished life because of her absent husband, a philanderer who kept failing kwageo (Joseon’s civil exam at the time). Kim wrote a number of poems about such financial challenges, including “Begging the Magistrate for Rice.”

Kim Keum-Won (김금원 / 金錦園) (1817-?) is a Korean poet of the late-Joseon dynasty who dressed up as a man in order to travel the Keum-Gang Mountains and the East Sea, after which she wrote a travelogue Ho-Dong-Seo-Nak-Ki (호동서락기 / 湖東西洛記 ). Born to a courtesan mother, Kim had limited future prospects but also seemed to benefit from more parental leniency because of her lower class, hence her crossdressing and adventurous trip. Afterward, she became known for this daring trip and also founded Joseon’s first association of female poets, Samhojeongsisa (삼호정시사 / 三湖亭詩社). Kim Keum-Won is a name she chose for herself and widely used, and her original name is unknown.

8 March 2022

Leave a Reply