Book Reviews: March 2013

Nervous Device, Poems by Catherine Wagner

Wedlocked, Memoir by Jay Ponteri

The Man Who Wouldn’t Stand Up, Fiction by Jacob M. Appel

Together We Jump, Fiction by Ken McAlpine

fff

Nervous Device

Nervous Device

Poems by Catherine Wagner

City Lights Books, 2012

ISBN-13: 978-0872865655

$13.95; 73pp.

Reviewed by Michael Martin Shea

Longtime readers of Catherine Wagner’s poetry will find themselves at home in the often-fragmented voice of Nervous Device, her fourth book, released in late 2012. In fact, the collection’s engagement with the type of disjunctive poetics that has hitherto characterized her work is comparatively neutered, at least when held next to the highly procedural poems-of-the-moment of My New Job—which is not to call it a step-down so much as a lateral move, more in line with the focused investigation of Macular Hole. Here, Wagner takes the idea of composition itself as her central object, beginning with the first poem, an ars poetica that quickly morphs into a faux (?) letter to her editor in which she quotes from her previous books. What becomes apparent is that, for Wagner, composition isn’t limited to the page—the poems exist as an extension of the self, which includes her physical self, imbuing the collection with a neurotic view of the body that’s become almost too commonplace for 21st century poets, as she claims: “writing a poem is like reaching two prosthetic limbs out as far as you can on either side to grab something in front of you,” or, elsewhere: “Thighs klutz beneath my skirt. // Dear art surface.”

In this way, “nervous device” signifies the speaker’s body as a type of machine—strangely calibrated, but machine-like all the same—and Wagner’s investigation of its output then expands to include all the factors that come to bear on production, ranging from the color spectrum to masturbation (a form of production, it seems). The collection is at its peak in the longer poems, especially “Pleasure Trip,” which switches between narrating an apparently autobiographical account of a failed marriage, a reading tour, and a relayed story of a character named Jeanne, whose relationship to the speaker is unclear. It is in this messy confluence of history, both past and present, that Wagner’s disjunctive vision becomes its own form of synthesis, the lack of resolution giving the poem a fullness by gesturing beyond the stories themselves. This vision even carries over to the language, which is specifically blocky and unadorned, allowing for moments of simplistic insight (“love is made of stuff. I’ll show you, I’ll give it to you in a bag”). It’s a poetics that calls to mind the structural analyses of George Oppen, as well as Alice Notley’s more-discursive/less-narrative tendencies, but Wagner is more flippant and playful than either of these writers—her predicament, as she names it: “wretched powerless / except to cause annoy. So cause annoy.”

To certain readers, these poems might well be productively frustrating. But for those with a background in non-linear, self-conscious poetics, the main cause of annoyance here is the familiarity. Wagner’s ability to shove beautiful lines where we don’t think they should go is consistently enjoyable, but the book itself feels static, especially when the poems focus on their own poem-hood (the dialogue-poem, “A Well is a Mine: A Good Belongs To Me,” especially comes to mind, with its kitschy use of math equations). Of course, the area of poetics Wagner hails from fundamentally rejects the idea of entertaining the reader or pandering to his/her expectations. Wagner herself claims at the book’s outset a desire to “unalign” from the “intuition track,” but it’s just not clear that she goes far enough. Nervous Device, on a poem-level, showcases a highly skilled poet at her craft; on a book-level, however, one wonders if a wider lens would have brought about a more engaging and challenging read.

Wedlocked

Wedlocked

Memoir by Jay Ponteri

Hawthorne Books and Literary Arts, 2013

ISBN-13: 978-0983850489

$16.95; 172 pp.

Reviewed by Renée K. Nicholson

Desire nests at the heart of Jay Ponteri’s Wedlocked, a memoir that explores the internal logic of fantasy and the more straightforward, binding ties of marriage. Ponteri explores the idea of marriage through the comparison of the mythical Frannie, a composite of the women that have fueled his desire, and the mixing of the invented and real worlds they inhabit. Frannie is the barista at the local café, the girl next door to his college apartment. She is the woman who lifts his sexual inhibitions, shares his passions—most notably books, without the constricting bonds of reality, credit card debt, home repair—to dampen his fantasy. She becomes the vehicle by which he can share his most intimate self, unfettered, emotionally rough hewn, and desired despite his imperfections and proclivities. As well, the creation of Frannie is an extension of the artist, the manifestation of creative impulses and the artist’s dwelling in the realm of imagination.

Instead of presenting Frannie against the backdrop of his wife, Ponteri inverts, presenting his wife and daily life as the other to his beloved invention. While Frannie is named, Ponteri presents his wife only as “my wife.” This distinction allows Ponteri to give voice and shape to the impulses and desires that define Frannie, opening himself to a self-revealing honesty that might not be achieved any other way. This approach allows us to explore his ache for Frannie as immediate, present yearning. The comparison of “the wife” to Frannie is less about these women, or what these women represent, than the confusing inner conflicts about marriage that Ponteri allows us to view, almost voyeuristically, through the manuscript. It is, in the simplest terms, a memoir of longing.

The narrative thrust of Wedlocked is the wife’s discovery of Ponteri’s manuscript, a project kept secret from her and which causes her a pain he can’t quite dismiss or reconcile. Often indifferent to the needs and wants of his wife, Ponteri also paints her as kind, dependable, a good mother to their son. And he does, in fact, desire her too, but not in the ways that we’ve come to accept as typical of marriage. The conflict fuels the reader’s understanding. Ponteri reveals how he understood his to be “marriage material,” returning to court her after dating other women, who, we might infer, become part of the Frannie fantasy. Ponteri does not always paint himself as sympathetic, exposing cruel tendencies and emotional distance, and yet his unflinching honesty makes him compelling. He can and will say the thing that otherwise wouldn’t be said.

Wedlocked also refuses the simplistic, truth-as-fact view of nonfiction. Instead its terrain is emotional and linked to artistic process: “Making art forces one to practice a kind of divergent thinking in which one considers many answers to a single question, many solutions to a single problem.” He confesses to both the act of making some stuff up, as well as upsetting or being hurtful to the reader. In this way, it stretches the confines of the so-called contract with the reader. His is a hard truth, and one that requires the latitude to be strictly true without always being factual, accuracy becoming an emotional construct. Sometimes filled with raw sexual ambition, other times quietly sad and contemplative, Ponteri dares memoir to go in a bold direction, with precedence on the intimacy between writer and reader.

The Man Who Wouldn’t Stand Up

The Man Who Wouldn’t Stand Up

Fiction by Jacob M. Appel

Cargo Publishing (Glasgow), 2012

ISBN-13: 978-1908885111

£8.99 UK ($14.13); 300pp.

Reviewed by Joe Ponepinto

Dr. Jacob M. Appel has published short stories in more than two hundred literary journals, many of them considered among the best in the genre. He’s won many literary contests and awards. In addition to being a prolific writer, he is a physician, attorney, and bioethicist. With The Man Who Wouldn’t Stand Up he adds his first novel to that list of accomplishments, and it’s almost no surprise the book received the 2012 Dundee International Book Prize.

The novel is a satire, premised on quiet, liberal botanist Arnold Brinkman’s unthinkable act—while attending a Yankee baseball game in spring 2004, amid lingering post-9/11 homeland fervor, he refuses to stand during the singing of “God Bless America.” When he notices a TV camera catching his defiance, he sticks out his tongue. To a nation paranoid about jihadists and foreign conspiracies, Arnold becomes the Tongue Terrorist. He is intractable, but although he’s right in his belief that he does not have to succumb to public opinion, he is hounded mercilessly by the media and the legal system which, in the anxiousness of those uncertain days, look for ways to prosecute, and thereby restore the public’s faith in the jingoistic way of life.

Worst among his tormentors is the Reverend Spotsylvania (Spotty) Spitford, leader of the Church of the Crusader, who makes Arnold his personal cause, acting as spokesman for a gaggle of self-appointed patriots who camp in front of the botanist’s house demanding an apology, or Arnold’s imprisonment, or both. Spitford is as hypocritical a character as they come, hiding the fact that he has two wives in separate cities—naturally he has designs on political office. But even when this fact is exposed he refuses to back down from his persecution of Arnold.

In this inventive and commercially appealing book, Appel sheds a harsh light on a society that allows its most vocal and least tolerant elements to form the basis of public opinion. (And he’s writing about 2004; what would he say about the nation nine years later?) The public’s leaders and officials offer no resistance to the will of the mob—they make no effort to reconcile the arbitrary values offered up as absolutes. Brinkman becomes, indeed, a man on the brink, forced to flee his home and wife, seeking refuge in the fringes of society.

It was all about borders. And Arnold was on the wrong side of them. He’d end up spending the rest of his life in an 8′ x 10′ cell, another darling of the Left like Mumia Au-Jamal or Lisl Auman, because he happened to be standing on one side of an arbitrary political boundary, a line as imaginary as the equator. In some countries, sticking out his tongue at the American flag would have made him a hero.

But the story isn’t a paean to brave souls who, despite a nation’s scorn, take a stand (so to speak). Appel deftly uses the leftist Arnold to also raise questions regarding the sacrosanct position of the individual in society: Where does personal freedom end? What is each person’s responsibility to society and family, and how do those needs balance against unadulterated truth? These are questions that would be well put to those who champion complete and unregulated individualism over the public good today. The idea of even a little self-sacrifice for the good of others seems lost in the antagonistic debates conducted in the public forum, but it is just beneath the surface in this book.

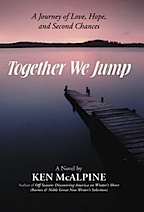

Together We Jump

Together We Jump

Fiction by Ken McAlpine

iUniverse Books, 2013

ISBN-13: 978-1475951219

$23.97 (hardcover); 361pp.

Reviewed by Vincent F.A. Golfin, Ph.D.

The subtitle for Ken McAlpine’s soon-to-be released novel, Together We Jump, is A Journey of Love, Hope and Second Chances. The 361-page work visits many locales throughout the United States, yet is more of a roller coaster ride through the mind and soul of the main character Pogue Whithouse, who as many over-age-60s, takes a physical, emotional, and psychological foray through the ghosts of relationships past in a bid for peace, or at least fulfillment, in the balance of his life.

Pogue seeks redemption, mainly about the death of his older brother Sean. The quest forces him to face the lies and secrets behind his relationships with many of the people he knew.

At one point, I thought the deeply personal nature of the experience and the book’s length were a fault. I wanted to give up the read, but McAlpine’s use of language and plot made every page turn. The narrative is poetic at turns, and the descriptions and reflections spur thoughts. Sea turtles’ life struggles serve as his metaphor, and the book mentions them at several junctures. Most die soon after they are born, yet those who survive beat the odds in a hostile world because of endurance. Pogue says:

In my favorite dream, I swim easily in green waters just below the surface so that the sky ripples overhead, the white clouds like bedsheets in the wind. I am underwater, but the river still sings on the surface, softer, dreamier, more distant, yet infinitely more comforting. I sense something timeless, beyond mankind’s stumblings, passed to me in a whisper I cannot grasp, but it soothes me nonetheless. I am gripped by something that swings on the very hinges of the earth, something so large it erases any urge to conquer, to compete, to dominate, to prove, to possess, to hate, to question.

The words and images are so real and human that readers will pause at many points to ask whether the book is a memoir. I did, more than a dozen times, but in the end, McAlpine’s tale is inspirational, not confessional.

The eerily realistic plot and dialogue only attests to the skills of a writer whose earlier works were largely nonfiction. McAlpine is a three-time winner of the Lowell Thomas Award for travel writing, and author of Islands Apart: A Year on the Edge of Civilization and Off Season: Discovering America on Winter’s Shore, a 2004 Barnes & Noble Discover Great Writers selection. Together We Jump and Fog, a novel also published through iUniverse last year, signal his foray into fiction.