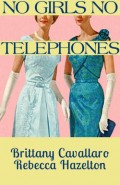

Book Review: No Girls No Telephones by Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton

No Girls No Telephones

Poems by Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton

Black Lawrence Press, September 2014

ISBN-13: 978-1625579997

$8.95; 28pp.

Reviewed by Andrew Purcell

In Matthew Buckley Smith’s essay, “Why Poems Don’t Make Sense,” which can be found in 32 Poems, he explains what sense is, how it differs from logic, and what nonsense entails, while illuminating the concept of theory of mind in relation to poetry.

When I first read Smith’s essay, I was also in the midst of reading No Girls No Telephones (Black Lawrence Press, 2014) by Brittany Cavallaro and Rebecca Hazelton. A collaborative chapbook of paired poems that take their shared titles from lines of Berryman, NGNT comes with an author’s note at the end that I’ll reproduce here in full:

Authors’ Note:

Brittany had the idea of writing an opposite imitation of a John Berryman Dream Song, and suggested that Rebecca write an opposite of that opposite. It was a strange game of literary translation, and by the end, it was hard to know who’d written what. These poems are an homage to Berryman’s singular syntax and diction, and our own engagement with it.

As Simone Muench notes in her back-cover blurb, the poems operate as a game of telephone to filter the sense of John Berryman’s poems through Cavallaro and Hazelton’s minds. The authors’ note explains the process whereby noise was added to the system, so to speak, with opposites of opposites reflecting off one another to introduce distortion. Just like in the game of telephone, the message at times becomes garbled well beyond lyricism, crossing into true nonsense. I tried all the standard ways of maximizing the poems’ content: reading aloud to myself, reading to someone else, reading out of order. Often, I noticed that sense slipped away as the poems progressed. And yes, there’s a natural pleasure born of unexpected and unexpectable constructions, but I kept thinking about Smith’s essay and my aversion to nonsense.

So what’s wrong with nonsense? To me, it’s boring and smacks of a writer who, despite having nothing to say, nevertheless seeks an audience. While I’m only marginally familiar with Cavallaro, Hazelton’s poems are, in general, not merely sensible but often profound. Berryman may be ethereal or even transcendental but he isn’t nonsensical, and the best games of telephone retain echoes of the intended message despite the accidents of flawed transmission. The meaning had to be in there somewhere, and then, at last, I saw it.

There aren’t just structural parallels between the paired poems; they are like transparencies to be laid one over the other. I suspect my initial blindness to this came from holding too tightly to the game of telephone concept. I kept trying to understand the poems through that lens, however figurative, despite my deepening frustration. While I can certainly see how it was relevant to the composition of the book, it put me on false footing to assume this would be the most fruitful way to read the poems. This misstep was admittedly my own fault. The method of composition does not imply the method of interpretation.

What’s genuinely captivating about the book is how two strophes of nonsense, on opposing pages, would give rise to something sensible, if non-concrete, “sense without reference” as the philosophers put it, when considered simultaneously, and that this sensibility resonated as truly Berrymanesque. NGNT taught me something. Not in the way of aphorism or analogy, or any of the pleasant methods through which I expect to encounter a lesson in most poems, but by frustrating my understanding and then composing sense in a manner I had never before experienced. For instance, from “Moved In, Mostly:”

| Then she was not a small one. Seriously, she felt it. She didn’t stay. The Italian and the Japanese fairytales from German and Russian fairytales separated, though some were allowed to shatter. |

Then he was not not an old one. False, he said. Then he left. The nowhere and underneath news-stories from Madison and Milwaukee news-stories congealed and none were left to pair off as they wanted. |

This pattern of Cavallaro and Hazelton playing with opposites continues throughout NGNT. I’m fascinated by opposites, not so much in the antonymic dark/light, light/heavy, land/sea kinds of couplings, but when we think, for example, of the opposite of a park. The first thing that comes to my mind is wasteland, but what about office as the opposite of park? Or something cheeky like carpark, where car acts as a prefix meaning anti? This way of thinking can work as a lever for the imagination. For instance, what if the opposite of plant is not animal, but something that thrives on moonlight and vodka? The opening lines of the poems “Mission Accomplished” demonstrate this effect to highlight a mode of seeing and thinking that is acutely poetic:

Her inner life was left on a marked tree | Our outer hearts are found in an unmarked grave

Reading NGNT was non-recreational but rewarding. The chapbook expanded the possibilities of nonsense in ways far more sophisticated than the attempts made in the vast bulk of conceptual poetry I’ve come across. The derivation of felt meaning from compounded lines that bordered on nonsense or were nonsense, surprised and delighted me. When you also consider the back-and-forth reflection aspect of the process, you start to realize that this chapbook represents an intellectual acrobatics performance by Cavallaro and Hazelton, who have coyly veiled the high-concept aspect of their project with the pink toile of play.

Andrew Purcell‘s work has appeared in The Adirondack Review, Birdfeast, The Baltimore Review, NightBlock, and Weave Magazine, among others. He received his MFA from Syracuse University and now lives and works in Philadelphia.