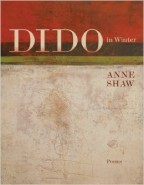

Book Review: Dido in Winter by Alix Anne Shaw

Dido in Winter

Poems by Alix Anne Shaw

Persea Books, April 2014

ISBN-13: 978-0892554298

$15.95, 96pp.

Reviewed by Ryan Boyd

Dido in Winter by Alix Anne Shaw (a writer and sculptor based in Chicago) reminds you of the potential of human love and art. That probably sounds corny. But I found the book more enjoyable and intelligent than most of the new poetry I’ve read recently. Now, the text often is “desolate and inflamed,” as the publisher’s blurb asserts, but not for its entirety: there are significant stretches of hope, happiness, and wonder that make the prevailing tension bearable. The speaker of “Outage” hisses, “Fuck acceptance. Fuck you, letting go. I’ll surrender to the moment / when the moment starts to live up to its name” (original italics), but she’s also keen on possibilities of rebirth through organic locality: “I mean to cultivate / a backyard full of sisal and avocado trees.” Dido in Winter is cautious and half-cynical, with a sense that better worlds exist somehow, somewhere. The volume’s chary attitude toward love is exemplified by “Detachment,” which chews over a temporary bonding, perhaps a one-night-stand: “Hold me, stranger. Press me close / in the pearly morning light. I will dream us coffee, / the paper, pears.” She pines for “a modest setting-forth,” because “Last night you put your hands / around my neck. Tell me this was beautiful. / Say we wake unscathed.”

It’s a reliably compelling human trope, failed love, one of those disasters everyone gets around to eventually. The precise biographical nature of the speaker’s relationship—framed loosely by the story of Aeneas betraying Carthage’s queen—does not matter all that much, if a speaker can even be said to have a biography. More noteworthy is the way Shaw conjures and renders shareable some individual experience of pain without being sentimental or bitter. Dido’s tenor resonates widely, but none of it seems generic; the poetry flows from a lived experience stabilized and transmitted through art.

The volume often typographically spreads out its stanzas and couplets and sometimes uses fractured individual lines; occasionally it sounds like the verse of a more psychologically intense Amy Clampitt. Nature is all over these poems, yet I wouldn’t call Shaw a “nature poet.” Her work’s valence is human and generally urban, as with “Switch,” where “descriptions of the city” serve “to offset the protagonist’s despair.” She deploys meter when she wants to, as in the loosely iambic stretches of “City You Won’t Come Back To”: “All that rust and stubble, / all that riff and tear. For now, let’s walk where elm trees net the vacant lot. / For now, let’s traipse out barefoot, gummy tarmac blackening our heels” (emphasis added). Her ominous cinematic imagery might remind you of Charles Simic. Often she explicitly draws upon the metaphor of film, as with “Another Art House Movie,” with its eerie scenes (“Your room is a room / In shambles: a table set with stones, a steaming pan, a nail, a crust of bread”), or “A 16mm Film (in Black & White),” which looks like something out of Ingmar Bergman: “Hanks of salt grass, grainy rock, / silver wash of light along the bridge. / A hand grips rebar, the window breaks, then it all goes black. / Someone sobbing in another room— / This isn’t the end of the movie.”

Besides the gorgeous individual lines and images, the book is architecturally interesting, because multiple poems talk to and against one another. Take “Dido to the Little Matchgirl” and “Contrivance (Matchgirl’s Reply).” The former drags a chill of bitter advice, while the latter is flippant with an undercurrent of worry. “[Y]ou can be queen / of the airwaves, and still the signal’s weak,” Dido warns. “Don’t like / yourself too much” is her counsel for the “dirty / little bitch.” The matchgirl responds ironically, asking, “It’s not enough / to be a girl / I have to be good at it too?” “Self Portrait as Dido” is one of the best pieces, translating the speaker’s experience into a more public discourse of pain and slow recovery. Tellingly, the poem is in the third person, distancing the speaker from herself and suggesting that the reader might inhabit a comparable psychic space:

She has come at last to a flickering place

………….where sun swirls on the rockface by the spring

moving its blue and yellow hands

………….then vanishing, adept, adept

The way desire passes her

………….over now, aloof [. . .]

In places some readers might find the book inscrutable almost to a fault, as in the second stanza of “Alcove,” which tumbles into a vagueness that the typography does not clarify:

How the river glints like metal these residues

of speech my life

returned to me I don’t know why—

In “Ransom” the speaker is “Awash between sunder and edgeless / don’t tell them what was fastened / in my eye.” Awash where, now? “Bird & Hand” contains a legitimate howler: the speaker contemplates “the jizz of stars.” But as Auden once said, even great poets write bad lines, and Dido in Winter rarely stumbles. Whatever flaws it has are scattered and minor distractions indeed.

Ryan Boyd (@ryanaboyd) lives in Los Angeles and teaches at the University of Southern California. Read more of his work at thegeneralreader.com and ryanboydpoetry.com.