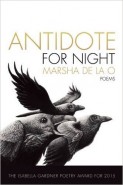

Book Review: Antidote for Night by Marsha de la O

Antidote for Night

Poems by Marsha de la O

BOA Editions, Ltd., September 2015

ISBN-13: 978-1938160813

$16.00; 88pp.

Reviewed by Lee Rossi

In the title poem of Marsha de la O’s new book, there is no antidote for night. Night—the domain of dream and death—is the price we pay for life and imagination. It is the without which not of art and love, and we make our accommodation with it as best we can. No one knows what terror or delights the next dreamscape will offer, and part of the charm of de la O’s poems is their utter unpredictability. She has studied her Neruda and Vallejo and concluded that the art of poetry involves giving readers not what they want but what they need.

“Say Nothing,” for instance, begins as a warning, an addendum to the old wives’ injunction against public displays of happiness. “Whatever I want the world will take away from me . . . ,” she begins, channeling her inner crone. And yet, how can she not praise “the steady slap of [her lover’s] heart . . . soft enough to sob for water . . . our two bodies . . . all that wet splendor.” She scares herself (“should I be saying this?” she asks, again in the voice of the crone), but not so much as to refrain from praising.

Faithful to the advice of Robert Bly, that early translator of the Spanish-language surrealists and advocate of ‘leaping poetry,’ de la O braids narrative, weaving rhythm and melody into un-ravel-able wholes. “Whistle Keeps on Blowing,” a meditation on the life and art of jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong, begins in the middle, jumps to the end, circles back to the beginning, and then returns to the middle, that apotheosis of life and art at the fullest:

the beautiful attack, horn straying only slightly from melody,

that first element, a rush of breath in the mouth

of water, I got a mind to leave this world /

and I got a mind to stay

This is a magical book, not just because witches and magic figure in the poems, but because the poems themselves are charms, incantations, hexes and prayers. They offer an old-fashioned remedy for a contemporary soul sickness. In “This Time” the poet conjures the image of a woman standing on a high balcony and contemplating suicide. Before she makes her fatal leap she considers the sun, her “eyes locked on radiance.” “Let her body open,” the poet prays, “enough to receive that one particle of joy.”

If one key to a poet’s sensibility is her diction, then de la O inhabits a fallen world, hers a vocabulary of blemish. The choice of “smudged,” “wickered,” and “blue-skeined,” the piling of “slump” and “shoal” and “thumbprint” all in one short poem (“Homesteader”) speaks to her sense of limits, more pagan than Christian. She inhabits a world before science, a world where a man can “dip his paw into the icy rush” of snow melt, “and with one swipe become [a] father” (“To the Unborn Child”).

It is a world saturated with primal fear. “I can hear their voices . . . ,” the poet says in “Coyote Song”:

unhinged saints gabbling to their shadows,

or panty-sniffers, drug-trippers in all flavors

past vanilla, . . . a pack of lunatics

crooning norteno songs.

What is certain is advent.

They’re coming down,

………………coming towards

the heart beneath the feathers,

coming for

what can’t be protected,

on a beam of dread.

But in addition to the fear there’s also “the urge to let loose, blow this little settlement, go wild.”

It is this earth, its fullness and its losses, that she sings. Her people, events, and themes are common enough—parents, children, lovers, illness and death—but they are translated out of a modern context (as in “What It Takes”), “to a place where words trail off in a tangle of fireweed and sumac.” Science, technology, media and manners have no lasting impact here on this deeper humanity. Witches and curses are as real as DNA. “She sprang out of the pine plank table at Nana’s house, a witch with a rope around her neck,” we are told in “I Have Not Said If I Believe,” a title whose ambivalence guides us through these harrowing evocations.

What hope there is resides in some fundamental, primeval human stirrings, near or at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy. “Hunger is the first and last word,” she insists in “How to Go On.” When everything else is gone, the reader is advised to buy a yam: “Pay attention to the name . . . – red jewel or ruby or red garnet. . . Wait until the sugar begins to burn on the oven wall. . . . This waiting can nourish you.” If you do as the witch / crone / poet commands, “It will be enough.” And for those of us who read this book these poems are more than enough.

Lee Rossi is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Wheelchair Samurai (Plain View Press), as well as numerous reviews and interviews. He lives in Northern California.